| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

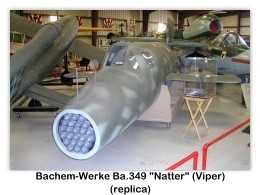

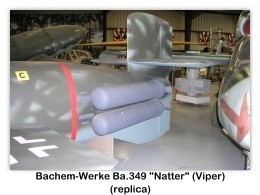

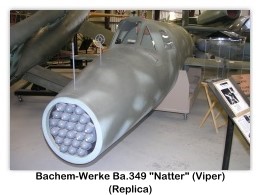

Bachem-Werke Ba.349 Natter (Viper)

World War II German Experimental Point-Defense Rocket-Powered Interceptor Aircraft

Archive Photos

Bachem-Werke Ba.349 Natter (Viper) c.2003 at the Planes of Fame Air Museum, Chino, CA

Overview

The Bachem Ba.349 Natter (Adder) was a World War II era German experimental point-defense rocket-powered interceptor aircraft which was to be used in a very similar way as unmanned surface-to-air missiles. After vertical takeoff which eliminated the need for airfields, the majority of the flight to the bombers was radio controlled from the ground. The primary mission of the (inexperienced) pilot was to aim the aircraft at its target bomber and fire its armament of rockets. The pilot and the main rocket engine should then land under separate parachutes, while the wooden fuselage was disposable. The only manned test flight, on 1 March 1945, ended with test-pilot Lothar Sieber being killed.

Development

With Luftwaffe air superiority being challenged by the Allies even over the Reich in 1943, radical innovations were required to overcome the crisis. Surface-to-air missiles appeared to be a very promising approach to counter the Allied bombing offensive and various projects were started, but invariably problems with the guidance systems and fusing prevented these from seeing widespread use. Providing the missile with a pilot who could control the weapon during the critical terminal approach phase offered a solution and was requested by the Luftwaffe in early 1944, under the Emergency Fighter Program.

A number of simple designs were proposed, most using a prone pilot to reduce frontal area. The front runner for the design was initially the Heinkel P.1077 Julia that took off from a rail and landed on a skid like the Messerschmitt Me.163 Komet.

Bachem Proposal

Erich Bachem’s BP20 was a development from a design he worked on at Fieseler, but considerably more radical than the other offerings. It was built using glued and screwed wooden parts with an armored cockpit, powered by a Walter HWK 509A-2 rocket, similar to the one in the Me.163. Four jettisonable Schmidding rocket boosters were used for launch, providing a combined thrust of 4,800 kgf (47 kN or 10,600 lbf) for 10 seconds before they were jettisoned. The aircraft rode up a rail for about 25 meters, by which time it was going fast enough for the aerodynamic flight controls to keep it flying straight.

The aircraft took off and was guided almost to the bomber’s altitude using radio control from the ground, with the pilot taking control right at the end to point the nose in the right direction, jettison the plastic nose cone and pull the trigger. This fired a salvo of rockets (either 33 R4M or 24 Henschel Hs.217), at which point the aircraft flew up and over the bombers. After running out of fuel the aircraft would then be used to ram the tail of a bomber, with the pilot ejecting just before impact to parachute to the ground.

Despite its apparent complexity, the design had one decisive advantage over the competitors — it eliminated the necessity to land an extremely fast rocket aircraft at an air base that, as the history of the Me.163 demonstrated, was extremely vulnerable against air raids.

Modifications

After Bachem’s design caught the eye of Heinrich Himmler at the SS, it emerged as the winner of the design contest. The Luftwaffe nevertheless managed to include some minor redesigns to try to save as much of the aircraft as possible, as well as eliminating the ramming attack.

The resulting tiny aircraft was fired up a 50-foot (15 meter) tall, open-structure launch tower, that had three vertical tracks that engaged the wing tips and the ventral fin’s lower edge, with the help of four solid fuel rockets (Schmidding), at the end of which it was already going fast enough for its control surfaces to work. The RATO boosters burned out after 12 seconds, at which point the main engine was long up to full thrust. Mission control now had the aircraft guided by radio to a point in front and above the bombers, where the pilot would turn off the autopilot, and push over for a gliding attack. After firing its armament of rockets it continued gliding down at high speed to about 3,000 m (10,000 ft), at which point the aircraft "broke" when a large parachute opened at the rear of the aircraft, popping off the nose section and the pilot with it. The pilot and the tail with the engine would land under their separate parachutes, and only the nose and the fuselage with the wooden wings were disposable.

At Schloss Ummendorf near Biberach an der Riß scientists of Technische Hochschule Aachen under Professor Wilhelm Fucks calculated the Natter’s aerodynamics with a large Analog computer while the RATO engines were tested at the Bachem-Werke factory in Waldsee. The Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt (DVL) in Braunschweig provided Wind-tunnel testing of models which were built early in the program. The results returned to the Bachem designers were that it would be "satisfactory" up to speeds of about Mach 0.95 or 685 mph, i.e. close to the sound barrier.

Testing

Full sized models were then completed and started flight testing on 3 November 1944 in Neuburg an der Donau. The initial prototype BP-20 M1 did not include an engine, and was towed up to 3000 meter by a Heinkel He.111 bomber for glide testing by Erich Klöckner. Klöckner managed to bail out as planned, and stated that it handled well over 200 km/h. Only the center of gravity and the fixing of pulling wires caused concerns.

Other test articles were equipped with extra solid motors for launch and autopilot tests. All of these went well, but during testing it was shown that any attempt to re-use the engine was hopeless; the impact speed was simply too high.

Until 27 January 1945 several manned and unmanned gliding flights after having been towed or released from a Mistel were conducted. Also, the unmanned vertical takeoff starts powered by rockets, which started on 18 December 1944 on Truppenübungsplatz Lager Heuberg near Stetten am kalten Markt were completed, as well as tests of the weapons. The distance from the Bachem factory in Waldsee to Heuberg was only 50 kilometers.

First Manned Test Flight

Construction of the production Ba.349A models had already started in October, and fifteen were launched over the next few months. Each launch resulted in some small modification to the design, and eventually these were collected into the definitive production version, the Bachem Ba.349B Natter which started testing in January.

In February 1945 the SS funders decided that the program was not going fast enough, and demanded a manned launch later that month. The only time that the aircraft was tested in this way was on March 1, when Lothar Sieber flew Ba.349A-M23, which was launched from the Lager Heuberg military training area near Stetten am kalten Markt. Things went well at first, but one of the jettisonable Schmidding boosters failed to release and the Natter got out of control. At 500 m (1,600 ft) the cockpit canopy pulled off as Sieber intended to bail out. He was instructed by radio to keep trying to shake off the booster, but inside the clouds he lost orientation. Also, the parachute did not open due to the stuck booster. Eventually, the aircraft turned over and slammed into the ground, killing Sieber. It is suspected that Sieber may have broken the sound barrier on the way down.

The cause was explained as a failure of the canopy which may simply not have been properly latched before launch. Photos were altered to hide the fact that a FuG16 radio was in the cockpit, used to order Sieber not to bail out. Excavations in 1998 found remains of the booster. Of the 36 Natter that had been built, 18 were used in unmanned tests, and two crashed with pilots, one during a glide and one with Sieber. Of the remaining 16, ten were burned at the end of the war while four were captured by Americans, one went to Britain and one ended up with the Russians. Of the four American aircraft, a pilotless version, is reported to have been fired aloft at Muroc Army Air Base in 1946. It would have crash landed somewhere near Las Vegas.

Legacy

US forces overran the factory at Waldsee in April, but small numbers of Bachem staff had moved and taken the remaining ten B models with them. Soon the US had caught up with them again and captured four, as six of the ten were burnt.

Several sources claim that an operational unit of Natters was set up by volunteers in Kirchheim unter Teck but didn’t carry out any operations, but the evidence for this is inconclusive.

Coincidentally, in Japan during the last days of the Pacific War, the Mizuno aircraft company under orders from the Imperial Japanese Navy developed an aircraft similar to the Natter. The Mizuno Shinryu suicide-interceptor rocket aircraft was the result. It would have been armed with air-to-air unguided rockets mounted under its wings and used, like the Natter, for interception of enemy aircraft, as well as a nose mounted warhead to be used for a suicide attack.

Natter Launch Pads at Kirchheim (Teck)

There are three launch pads for the Bachem Ba.349 Natter in the Hasenholz forest near Kirchheim/Teck. They are all that remain from the active launch site constructed in 1945. The three launch pads are arranged in the form of an equilateral triangle, whose sides point toward the east and the south. The distance between the launch pads is approximately 50 meters. The circular concrete pads on which the Bachem Ba.349s and their launch towers once stood still exist. In the center of each of the three concrete plates is a square hole approximately 50 centimeters deep, which once served as the foundation for the launch tower. Beside each hole is a pipe, cut off at ground level, which was probably once a cable pit. The Natter launch pads at Kirchheim (Teck) might be the only remnants of these rocket launch pads still on publicly accessible terrain The former test site for the Natter in Baden-Württemberg on the Heuberg near Stetten am kalten Markt is in an active military area, and therefore not accessible to tourists.

Surviving Aircraft

Three Bachem Ba.349A Natters survive today. Two can be found in the USA:

Specifications and Performance Data

General Characteristics

Dimensions

Weights

Powerplants

Performance

References