| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

North American P-51D Mustang (NA-109)

WWII single-engine single-seat long-range monoplane escort fighter

Archive Photos

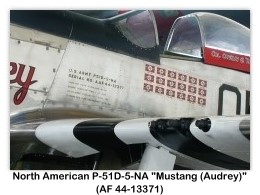

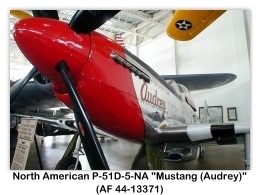

North American P-51D-5-NA Mustang (Audrey) (NA-109, AF 44-13371, c/n 109-27004) on display (11/26/2001) at the Hill Aerospace Museum, Hill AFB, Roy, Utah (Photo by John Shupek)

North American P-51D-10-NA Mustang (NA-109, AF 44-14826, c/n 109-28459, N551D) on display (4/14/2004) at the Tillamook Naval Air Museum, Tillamook, Oregon (Photo by John Shupek)

Overview

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang was an American long-range, single-seat fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II, the Korean War and several other conflicts. During World War II, Mustang pilots claimed 4,950 enemy aircraft shot down.

It was conceived, designed and built by North American Aviation (NAA), under the direction of lead engineer Edgar Schmued, in response to a specification issued directly to NAA by the British Purchasing Commission; the prototype NA-73X airframe was rolled out on 9 September 1940, albeit without an engine, 102 days after the contract was signed and first flew on 26 October.

The Mustang was originally designed to use the Allison V-1710 engine, which had limited high-altitude performance. It was first flown operationally by the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a tactical-reconnaissance aircraft and fighter-bomber. The addition of the Rolls-Royce Merlin to the P-51B/C model transformed the Mustang’s performance at altitudes above 15,000 ft, giving it a performance that matched or bettered the majority of the Luftwaffe’s fighters at altitude. The definitive version, the P-51D, was powered by the Packard V-1650-7, a license-built version of the Rolls-Royce Merlin 60 series two-stage two-speed supercharged engine, and armed with six 0.50 caliber (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns.

From late 1943, P-51Bs (supplemented by P-51Ds from mid-1944) were used by the USAAF’s Eighth Air Force to escort bombers in raids over Germany, while the RAF’s 2 TAF and the USAAF’s Ninth Air Force used the Merlin-powered Mustangs as fighter-bombers, roles in which the Mustang helped ensure Allied air superiority in 1944. The P-51 was also in service with Allied air forces in the North African, Mediterranean and Italian theaters, and saw limited service against the Japanese in the Pacific War.

At the start of Korean War, the Mustang was the main fighter of the United Nations until jet fighters such as the F-86 took over this role; the Mustang then became a specialized fighter-bomber. Despite the advent of jet fighters, the Mustang remained in service with some air forces until the early 1980s. After World War II and the Korean War, many Mustangs were converted for civilian use, especially air racing.

Design and Development

Genesis

In April 1938, shortly after the German Anschluss of Austria, the British government established a purchasing commission in the United States, headed by Sir Henry Self. Self was given overall responsibility for Royal Air Force (RAF) production and research and development, and also served with Sir Wilfrid Freeman, the "Air Member for Development and Production". Self also sat on the British Air Council Sub-committee on Supply (or "Supply Committee") and one of his tasks was to organize the manufacturing and supply of American fighter aircraft for the RAF. At the time, the choice was very limited, as no U.S. aircraft then in production or flying met European standards, with only the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk coming close. The Curtiss-Wright plant was running at capacity, so P-40’s were in short supply.

North American Aviation (NAA) was already supplying its Harvard trainer to the RAF, but was otherwise under utilized. NAA President "Dutch" Kindelberger approached Self to sell a new medium bomber, the B-25 Mitchell. Instead, Self asked if NAA could manufacture the Tomahawk under license from Curtiss. Kindelberger said NAA could have a better aircraft with the same engine in the air sooner than establishing a production line for the Curtiss P-40. The Commission stipulated armament of four 0.303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns, the Allison V-1710 liquid-cooled engine, a unit cost of no more than $40,000, and delivery of the first production aircraft by January 1941. In March 1940, 320 aircraft were ordered by Sir Wilfred Freeman who had become the executive head of Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), and the contract was promulgated on 24 April.

The design, known as the NA-73X, followed the best conventional practice of the era, but included several new features. One was a wing designed using laminar flow airfoils which were developed co-operatively by North American Aviation and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). These airfoils generated very low drag at high speeds. During the development of the NA-73X, a wind tunnel test of two wings, one using NACA 5-digit airfoils and the other using the new NAA/NACA 45-100 airfoils, was performed in the University of Washington Kirsten Wind Tunnel. The results of this test showed the superiority of the wing designed with the NAA/NACA 45-100 airfoils. The other feature was a new radiator design that exploited the "Meredith Effect", in which heated air exited the radiator as a slight amount of jet thrust. Because NAA lacked a suitable wind tunnel to test this feature, it used the GALCIT 10 ft (3.0 m) wind tunnel at Caltech. This led to some controversy over whether the Mustang’s cooling system aerodynamics were developed by NAA’s engineer Edgar Schmued or by Curtiss, although NAA had purchased the complete set of Curtiss P-40 and Curtiss XP-46 wind tunnel data and flight test reports for US$56,000. The NA-73X was also one of the first aircraft to have a fuselage lofted mathematically using conic sections; this resulted in the aircraft’s fuselage having smooth, low drag surfaces. To aid production, the airframe was divided into five main sections’forward, center, rear fuselage and two wing halves’all of which were fitted with wiring and piping before being joined.

The prototype NA-73X was rolled out in September 1940 and first flew on 26 October 1940, respectively 102 and 149 days after the order had been placed, an uncommonly short gestation period. The prototype handled well and accommodated an impressive fuel load. The aircraft’s two-section, semi-monocoque fuselage was constructed entirely of aluminum to save weight. It was armed with four 0.30 in (7.62 mm) M1919 Browning machine guns, two in the wings and two mounted under the engine and firing through the propeller arc using gun synchronizing gear.

While the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) could block any sales it considered detrimental to the interests of the US, the NA-73 was considered to be a special case because it had been designed at the behest of the British. In September 1940 a further 300 NA-73s were ordered by MAP. To ensure uninterrupted delivery Colonel Oliver P. Echols arranged with the Anglo-French Purchasing Commission to deliver the aircraft, and NAA gave two examples to the USAAC for evaluation.

Operational History

U.S. Operational Service

Pre-war Theory

Pre-war doctrine of most bomber forces was to attack at night when the bombers would be effectively immune to interception. The loss in accuracy due to limited visibility was a high price to pay, protecting small targets from attack. The only targets that could be attacked were large ones, effectively whole cities. As "the bomber will always get through", the future of war was believed to consist of large fleets of bombers pounding each other’s cities night after night. The Royal Air Force based its development policy on this concept, developing a series of dedicated night bombers.

There were those that dismissed this concept as immoral and continued to press for precision attacks on strategic targets as the most effective means of waging war. The RAF did attempt several long-range daylight raids early in the war using the Vickers Wellington, but suffered such high casualties that they abandoned the effort quickly. The Luftwaffe had the advantage of bases in France that allowed their fighters to escort the bombers at least part way on their missions. This strategy proved ineffective, as the RAF fighters ignored the escorts and attacked the bombers. The Germans abandoned day bombing and switched to night bombing during The Blitz of 1940-41. By the end of 1940, it appeared that daylight strategic bombing was ineffective.

American pre-war doctrine developed out of an isolationist policy that was primarily defensive. The B-17 had originally been designed to attack shipping at long range from U.S. bases. For this role it needed to be able to attack in daylight and used the advanced Norden bombsight to improve accuracy. As the bomber developed, more and more defensive armament was added to outgun the fighters it would face. In light of this heavy defensive firepower, the USAAC came to believe that tightly packed formations of B-17s would have so much firepower that they could fend off fighters on their own. In spite of evidence to the contrary from the RAF and Luftwaffe, this strategy was believed to be sound. When the U.S. entered the war they put this strategy into force, building up a strategic bomber force based in Britain.

Trial by Fire

The 8th Air Force started operations from Britain in August 1942. At first, because of the limited scale of operations, there was no conclusive evidence that the American doctrine was failing. In the 26 operations which had been flown to the end of 1942 the loss rate had been under 2%. This rate was better than the RAF’s night efforts, and similar to the losses one would expect due to mechanical failure.

In January 1943, at the Casablanca Conference, the Allies formulated the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) plan for "round-the-clock" bombing by the RAF at night and the USAAF by day. In June 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued the Pointblank Directive to destroy the Luftwaffe before the invasion of Europe, putting the CBO into full implementation. Following this, the 8th Air Force’s heavy bombers conducted a series of deep-penetration raids into Germany, beyond the range of escort fighters.

German daytime fighter efforts were, at that time, focused on the eastern front and several other distant locations. Initial efforts by the 8th met limited and unorganized resistance, but with every mission the Luftwaffe moved more aircraft to the west and quickly improved their battle direction. The Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission in August lost 60 B-17s of a force of 376, the October 14 attack lost 77 of a force of 291, 26% of the attacking force. Losses were so severe that long-range missions were called off.

The solution was understood - escorting fighters could break up attacks by fighters before they could reach the bombers. The Lockheed P-38 Lightning had the range to escort the bombers, but was only available in small numbers in the European theater due to its Allison engines proving difficult to maintain. It was also a very expensive aircraft to build and operate. The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt was capable of meeting the Luftwaffe on more than even terms, but did not at the time have sufficient range. The Luftwaffe quickly identified its maximum range, and their fighters waited for the bombers just beyond the point where the Thunderbolts had to turn Back.

P-51 Introduction

The P-51 Mustang was a solution to the clear need for an effective bomber escort. The Mustang was at least as simple as other aircraft of its era. It used a common, reliable engine and had internal space for a huge fuel load. With external fuel tanks, it could accompany the bombers all the way to Germany and Back. Enough P-51s became available to the 8th and 9th Air Forces in the winter of 1943-44. When the Pointblank offensive resumed in early 1944, matters changed dramatically. The P-51 proved perfect for escorting bombers all the way to the deepest targets. The Eighth Air Force began to switch its fighter groups to the Mustang, first exchanging arriving P-47 groups for those of the 9th Air Force using P-51s, then gradually converting its Thunderbolt and Lightning groups. The defense was initially layered, using the shorter range P-38s and P-47’s to escort the bombers during the initial stages of the raid and then handing over to the P-51 when they turned for home. By the end of 1944, 14 of its 15 groups flew the Mustang.

The Luftwaffe initially adapted to the U.S. fighters by modifying their tactics, massing in front of the bombers and then attacking in a pass through the formation. Flying in close formation with the bombers, the P-51s had little time to react before the attackers were already running out of range. To better deal with the bombers, the Luftwaffe started increasing the armament on their fighters with heavy cannons. The additional weight decreased performance to the point where their aircraft were vulnerable if caught by the P-51s. At first, their defensive tactic was to avoid prolonged dogfights.

Destroying the Luftwaffe

General James Doolittle told the fighters in early 1944 to stop flying in formation with the bombers and instead attack the Luftwaffe wherever it could be found. The Mustang groups were sent in before the bombers, forming up well ahead of the bomber formations in an air superiority "fighter sweep" manner, and could hunt the German fighters while they were forming up. The results were astonishing; the Luftwaffe lost 17% of its fighter pilots in just over a week. As Doolittle later noted, "Adolf Galland said that the day we took our fighters off the bombers and put them against the German fighters, that is, went from defensive to offensive, Germany lost the air war."

The Luftwaffe answer was the Gefechtsverband (battle formation). It consisted of a Sturmgruppe of heavily armed and armored Fw.190s escorted by two Begleitgruppen of light fighters, often Bf.109s, whose task was to keep the Mustangs away from the Fw.190s attacking the bombers. This scheme was excellent in theory but difficult to apply in practice. The large German formation took a long time to assemble and was difficult to maneuver. It was often intercepted by the escorting P-51s using the newer "fighter sweep" tactics out ahead of the heavy bomber formations, breaking up the Gefechtsverband formations before reaching the bombers; when the Sturmgruppe worked, the effects were devastating. With their engines and cockpits heavily armored, the Fw.190s attacked from astern and gun camera films show that these attacks were often pressed to within 100 yds (90 m).

While not always able to avoid contact with the escorts, the threat of mass attacks and later the "company front" (eight abreast) assaults by armored Sturmgruppe Fw.190s brought an urgency to attacking the Luftwaffe wherever it could be found. Beginning in late February 1944, 8th Air Force fighter units began systematic strafing attacks on German airfields with increasing frequency and intensity throughout the spring with the objective of gaining air supremacy over the Normandy battlefield. In general these were conducted by units returning from escort missions but, beginning in March, many groups also were assigned airfield attacks instead of bomber support. The P-51, particularly with the advent of the K-14 Gyro gun sight and the development of "Clobber Colleges" for the training of fighter pilots in fall 1944, was a decisive element in Allied countermeasures against the Jagdverbände.

The numerical superiority of the USAAF fighters, superb flying characteristics of the P-51, and pilot proficiency helped cripple the Luftwaffe’s fighter force. As a result the fighter threat to US, and later British, bombers was greatly diminished by July 1944. Reichmarshal Hermann Göring, commander of the German Luftwaffe during the war, was quoted as saying, "When I saw Mustangs over Berlin, I knew the jig was up."

Mopping Up

On 15 April 1944, VIII FC began Operation Jackpot, attacks on Luftwaffe fighter airfields. As the efficacy of these missions increased, the number of fighters at the German air bases fell to the point where they were no longer useful targets and on 21 May, targets were expanded to include railways, locomotives and rolling stock used by the Germans to transport materiel and troops, in missions dubbed "Chattanooga". The P-51 excelled at this mission, although losses were much higher on strafing missions than in air-to-air combat, partially because like other fighters using liquid-cooled engines, the Mustang’s coolant system could be punctured by small arms.

Given the overwhelming Allied air superiority, the Luftwaffe put its effort into the development of aircraft of such high performance that they could operate with impunity. Foremost among these were the Messerschmitt Me.163 Komet rocket interceptors and Messerschmitt Me.262 jet fighter. In action, the Me.163 proved to be more dangerous to the Luftwaffe than to the Allies and was never a serious threat. The Me.262 was, but attacks on their airfields neutralized them. The jet engines of the Me.262s needed careful nursing by their pilots and these aircraft were particularly vulnerable during takeoff and landing. Lt. Chuck Yeager of the 357th Fighter Group was one of the first American pilots to shoot down a Me.262 which he caught during its landing approach. On 7 October 1944, Lt. Urban Drew of the 365th Fighter Group shot down two Me.262s that were taking off, while on the same day Lt. Col. Hubert Zemke, who had transferred to the Mustang equipped 479th Fighter Group, shot down what he thought was a Bf.109, only to have his gun camera film reveal that it may have been an Me.262.

The Mustang also proved useful against the V-1’s launched toward London. P-51B/Cs using 150 octane fuel were fast enough to catch the V-1 and operated in concert with shorter-range aircraft like advanced marks of the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Tempest.

By 8 May 1945, the 8th, 9th and 15th Air Force’s P-51 groups claimed some 4,950 aircraft shot down (about half of all USAAF claims in the European theater), the most claimed by any Allied fighter in air-to-air combat and 4,131 destroyed on the ground. Losses were about 2,520 aircraft. The 8th Air Force’s 4th Fighter Group was the top-scoring fighter group in Europe, with 1,016 enemy aircraft claimed destroyed. This included 550 claimed in aerial combat and 466 on the ground.

In air combat, the top-scoring P-51 units (both of which exclusively flew Mustangs) were the 357th Fighter Group of the 8th Air Force with 565 air-to-air combat victories and the Ninth Air Force’s 354th Fighter Group with 664, which made it one of the top scoring fighter groups. Martin Bowman reports that in the European Theater of Operations, Mustangs flew 213,873 sorties and lost 2,520 aircraft to all causes. The top Mustang ace was the USAAF’s George Preddy, whose final tally stood at 26.333, 23 scored with the P-51, when he was shot down and killed by friendly fire on Christmas Day 1944 during the Battle of the Bulge.

In China and the Pacific Theater

In 1943, P-51B joined the American Volunteer Group. In early 1945, P-51C, D and K variants also joined the Chinese Nationalist Air Force. These Mustangs were provided to the 3rd, 4th and 5th Fighter Groups and used to attack Japanese targets in occupied areas of China. The P-51 became the most capable fighter in China while the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force used the Ki-84 Hayate against it.

The P-51 was a relative latecomer to the Pacific Theater. This was due largely to the need for the aircraft in Europe, although the P-38s Twin-engine design was considered a safety advantage for long over-water flights. The first P-51s were deployed in the Far East later in 1944, operating in close-support and escort missions, as well as tactical photo reconnaissance. As the war in Europe wound down, the P-51 became more common: eventually, with the capture of Iwo Jima, it was able to be used as a bomber escort during B-29 missions against the Japanese homeland.

The P-51 was often mistaken for the Japanese Ki-61 Hien in both China and Pacific because of its similar appearance.

Expert Opinions

Chief Naval Test Pilot and C.O. Captured Enemy Aircraft Flight Capt. Eric Brown, CBE, DSC, AFC, RN, tested the Mustang at RAE Farnborough in March 1944, and noted, "The Mustang was a good fighter and the best escort due to its incredible range, make no mistake about it. It was also the best American dogfighter. But the laminar flow wing fitted to the Mustang could be a little tricky. It could not by no means out-turn a Spitfire. No way. It had a good rate-of-roll, better than the Spitfire, so I would say the plusses to the Spitfire and the Mustang just about equate. If I were in a dogfight, I’d prefer to be flying the Spitfire. The problem was I wouldn’t like to be in a dogfight near Berlin, because I could never get home to Britain in a Spitfire!"

Luftwaffe Experten were confident that they could outmaneuver the P-51 in a dogfight. Kurt Bühligen, the third-highest scoring German fighter pilot of the Second World War on the Western Front, with 112 victories, later recalled that "We would out-turn the P-51 and the other American fighters, with the (Bf) ’109’ or the (Fw) ’190’. Their turn rate was about the same. The P-51 was faster than us but our munitions and cannon were better."

Post-World War II

In the aftermath of World War II, the USAAF consolidated much of its wartime combat force and selected the P-51 as a "standard" piston-engine fighter, while other types, such as the P-38 and P-47, were withdrawn or given substantially reduced roles. As the more advanced (P-80 and P-84) jet fighters were introduced, the P-51 was also relegated to secondary duties.

In 1947, the newly-formed USAF Strategic Air Command employed Mustangs alongside F-6 Mustangs and F-82 Twin Mustangs, due to their range capabilities. In 1948, the designation P-51 (P for pursuit) was changed to F-51 (F for fighter), and the existing F designator for photographic reconnaissance aircraft was dropped because of a new designation scheme throughout the USAF. Aircraft still in service in the USAF or Air National Guard (ANG) when the system was changed included: F-51B, F-51D, F-51K, RF-51D (formerly F-6D), RF-51K (formerly F-6K), and TRF-51D (two-seat trainer conversions of F-6D’s). They remained in service from 1946 through 1951. By 1950, although Mustangs continued in service with the USAF after the war, the majority of the USAF’s Mustangs had become surplus to requirements and placed in storage, while some were transferred to the Air Force Reserve (AFRES) and the Air National Guard (ANG).

From the start of the Korean War, the Mustang once again proved useful. A substantial number of stored or in service F-51Ds were shipped, via aircraft carriers, to the combat zone and were used by the USAF, and the Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF). The F-51 was used for ground attack, fitted with rockets and bombs, and photo-reconnaissance, rather than being as interceptors or "pure" fighters. After the first North Korean invasion, USAF units were forced to fly from bases in Japan, and the F-51Ds, with their long range and endurance, could attack targets in Korea that short-ranged F-80 jets could not. Because of the vulnerable liquid cooling system, however, the F-51s sustained heavy losses to ground fire. Because of its lighter structure, and a shortage of spare parts, the newer, faster F-51H was not used in Korea.

Mustangs continued flying with USAF and ROKAF fighter-bomber units on close support and interdiction missions in Korea until 1953, when they were largely replaced as fighter-bombers by USAF F-84s, and by United States Navy (USN) Grumman F9F Panthers. Other air forces and units using the Mustang included the Royal Australian Air Force’s (RAAF)’s 77 Squadron, which flew Australian-built Mustangs as part of British Commonwealth Forces Korea. The Mustangs were replaced by Gloster Meteor F.8s in 1951. The South African Air Force’s (SAAF)’s 2 Squadron used U.S. built Mustangs as part of the U.S. 18th Fighter Bomber Wing, and had suffered heavy losses by 1953, after which 2 Squadron converted to the F-86 Sabre.

F-51s flew in the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard throughout the 1950’s. The last American USAF Mustang was F-51D-30-NA (AF 44-74936), which was finally withdrawn from service with the West Virginia Air National Guard in late 1956 and retired to what was then called the Air Force Central Museum, although it was briefly reactivated to fly at the 50th anniversary of the Air Force Aerial Firepower Demonstration at the Air Proving Ground, Eglin AFB, Florida, on 6 May 1957. This aircraft, painted as P-51D-15-NA (AF 44-15174), is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, in Dayton, Ohio,

The final withdrawal of the Mustang from USAF dumped hundreds of P-51s onto the civilian market. The rights to the Mustang design were purchased from North American by the Cavalier Aircraft Corporation, which attempted to market the surplus Mustang aircraft in the U.S. and overseas. In 1967 and again in 1972, the USAF procured batches of remanufactured Mustangs from Cavalier, most of them destined for air forces in South America and Asia that were participating in the Military Assistance Program (MAP). These aircraft were remanufactured from existing original F-51D airframes but were fitted with new V-1650-7 engines, a new radio fit, tall F-51H-type vertical tails, and a stronger wing that could carry six 0.50 in (13 mm) machine guns and a total of eight underwing hardpoints. Two 1,000 lb (454 kg) bombs and six 5 in (127 mm) rockets could be carried. They all had an original F-51D-type canopy, but carried a second seat for an observer behind the pilot. One additional Mustang was a two-seat dual-control TF-51D (67-14866) with an enlarged canopy and only four wing guns. Although these remanufactured Mustangs were intended for sale to South American and Asian nations through the MAP, they were delivered to the USAF with full USAF markings. They were, however, allocated new serial numbers (AF 67-14862/14866, AF 67-22579/22582 and AF 72-1526/1541).

The last U.S. military use of the F-51 was in 1968, when the U. S. Army employed a vintage F-51D (AF 44-72990) as a chase aircraft for the Lockheed YAH-56 Cheyenne armed helicopter project. This aircraft was so successful that the Army ordered two F-51Ds from Cavalier in 1968 for use at Fort Rucker as chase planes. They were assigned the serials AF 68-15795 and AF 68-15796. These F-51s had wingtip fuel tanks and were unarmed. Following the end of the Cheyenne program, these two chase aircraft were used for other projects. One of them (AF 68-15795) was fitted with a 106 mm recoilless rifle for evaluation of the weapon’s value in attacking fortified ground targets. Cavalier Mustang (AF 68-15796) survives at the Air Force Armament Museum, Eglin AFB, Florida, displayed indoors in World War II markings.

The F-51 was adopted by many foreign air forces and continued to be an effective fighter into the mid-1980’s with smaller air arms. The last Mustang ever downed in battle occurred during Operation Power Pack in the Dominican Republic in 1965, with the last aircraft finally being retired by the Dominican Air Force (FAD) in 1984.

Non-U.S. Service

After World War II, the P-51 Mustang served in the air arms of more than 55 nations. During wartime, a Mustang cost about $51,000 dollars, while many hundreds were sold postwar for the nominal price of one dollar to the American countries that signed the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, ratified in Rio de Janeiro in 1947. Following is a list of some of the countries that used the P-51 Mustang.

Australia

In November 1944, 3 Squadron RAAF became the first Royal Australian Air Force unit to use Mustangs. At the time of its conversion from the P-40 to the Mustang the squadron was based in Italy with the RAF’s First Tactical Air Force. By this time, the Australian government had also decided to order Australian-built Mustangs, to replace its Curtiss Kittyhawks and CAC Boomerangs in the South West Pacific theater. The Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) factory at Fishermans Bend, Melbourne was the only non-U.S. production line for the P-51.

In 1944, 100 P-51Ds were shipped from the U.S. in kit form to inaugurate production. From February 1945, CAC assembled 80 of these under the designation CA-17 Mustang Mark 20, with the first one being handed over to the RAAF on 4 June 1945. The remaining 20 were kept unassembled as spare parts. In addition, 84 P-51Ks were also shipped directly to the RAAF from the USA.

In late 1946 CAC was given another contract to build 170 (reduced to 120) more P-51Ds on its own; these, designated CA-18 Mustang Mark 21, Mark 22 or Mark 23, were manufactured entirely in-house, with only a few components being sourced from overseas. The 21 and 22 used the American-built Packard V-1650-3 or V-1650-7. The Mark 23’s, which followed the 21’s, were powered by Rolls-Royce Merlin 66 or Merlin 70 engines. The first 26 were built as Mark 21’s, followed by 66 Mark 23’s; the first 14 Mark 21’s were converted to fighter-reconnaissance aircraft, with two F24 cameras in both vertical and oblique positions in the rear fuselage, above and behind the radiator fairing; the designation of these modified Mustangs was changed from Mark 21 to Mark 22. An additional 14 purpose-built Mark 22’s, built after the Mark 23’s, and powered by either Packard V-1650-7s or Merlin 68s, completed the production run. All of the CA-17s and CA-18’s, plus the 84 P-51Ks, used Australian serial numbers prefixed by A68.

3 Squadron was renumbered 4 Squadron after returning to Australia from Italy and converted to CAC-built Mustangs. Several other Australian or Pacific based squadrons converted to P-51s from July 1945, having been equipped with P-40’s or Boomerangs for wartime service; these units were: 76, 77, 82, 83, 84 and 86 Squadrons. Only 17 Mustangs reached the RAAF’s First Tactical Air Force front line squadrons by the time World War II ended in August 1945.

76, 77 and 82 Squadrons were formed into 81 Fighter Wing of the British Commonwealth Air Force (BCAIR) which was part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) stationed in Japan from February 1946. 77 Squadron used its P-51s extensively during the first years of the Korean War, before converting to Gloster Meteor jets.

Five reserve units from the Citizen Air Force (CAF) also operated Mustangs. 21 "City of Melbourne" Squadron, based in the state of Victoria; 22 "City of Sydney" Squadron, based in New South Wales; 23 "City of Brisbane" Squadron, based in Queensland; 24 "City of Adelaide" Squadron, based in South Australia; and 25 "City of Perth" Squadron, based in Western Australia. The last Mustangs were retired from these units in 1960 when CAF units adopted a non-flying role.

In October 1953, six Mustangs, including A68-1, the first Australian built CA-17 Mk.20, were allotted to the Long Range Weapons Development Establishment at Maralinga, South Australia, for use in experiments to gauge the effects of low-yield nuclear atomic bombs. The Mustangs were placed on a dummy airfield about 0.62 mi (1 km) from the blast tower on which two low-yield bombs were detonated. The Mustangs survived intact. In 1967, A68-1 was bought by a U.S. syndicate, for restoration to flight status and is currently owned by Troy Sanders.

Bolivia

Nine Cavalier F-51D (including the two TF-51s) were given to Bolivia, under a program called Peace Condor.

Canada

Canada had five squadrons equipped with Mustangs during World War II. RCAF 400, 414 and 430 squadrons flew Mustang Mk.I’s (1942-1944), and 441 and 442 Squadrons flew Mustang Mk.III’s and Mk.IVs in 1945. Postwar, a total of 150 Mustang P-51Ds were purchased and served in two regular (416 "Lynx" and 417 "City of Windsor") and six auxiliary fighter squadrons (402 "City of Winnipeg", 403 "City of Calgary", 420 "City of London", 424 "City of Hamilton", 442 "City of Vancouver" and 443 "City of New Westminster"). The Mustangs were declared obsolete in 1956, but a number of special-duty versions served on into the early 1960’s.

China

The P-51 firstly joined the Chinese Nationalist Air Force during the late Sino-Japanese War to fight against the Japanese. After the war Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government used the planes against insurgent Communist forces. The Nationalists retreated to Taiwan in 1949. Pilots supporting Chiang brought most of the Mustangs with them, where the aircraft became part of the island’s defence arsenal. Taiwan subsequently acquired additional Mustangs from the USAF and other sources. Some Mustangs remained on the mainland, captured by Communist forces when the Nationalists left.

People’s Republic of China

See China above; the Chinese Communists captured 39 P-51s from the Chinese Nationalists as they were retreating to Taiwan.

Costa Rica

The Costa Rica Air Force flew four P-51Ds from 1955 to 1964.

Cuba

In November 1958, three US-registered civilian P-51D Mustangs were illegally flown separately from Miami to Cuba, on delivery to the rebel forces of the 26th of July Movement, then headed by Fidel Castro during the Cuban Revolution. One of the Mustangs was damaged during delivery, and none of them were used operationally. After the success of the revolution in January 1959, with other rebel aircraft plus those of the existing Cuban government forces, they were adopted into the Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria. Due to increasing U.S. restrictions, lack of spares and maintenance experience, they never achieved operational status. At the time of the Bay of Pigs invasion, the two intact Mustangs were already effectively grounded at Campo Columbia and at Santiago. After the failed invasion, they were placed on display with other symbols of "revolutionary struggle", and one remains on display at the Museo del Aire (Cuba).

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic (FAD) was the largest Latin American air force to employ the P-51D, with six aircraft acquired in 1948, 44 ex-Swedish F-51Ds purchased in 1948 and a further Mustang obtained from an unknown source. It was the last nation to have any Mustangs in service, with some remaining in use as late as 1984. Nine of the final 10 aircraft were sold Back to American collectors in 1988.

El Salvador

The FAS purchased five Cavalier Mustang II’s (and one dual control Cavalier TF-51) that featured wingtip fuel tanks to increase combat range and up-rated Merlin engines. Seven P-51D Mustangs were also in service. They were used during the 1969 Soccer War against Honduras, the last time the P-51 was used in combat. One of them, FAS-404, was shot down by a F4U-5 flown by Cap. Fernando Soto in the last aerial combat between piston engine fighters in the world.

France

In late 1944, the first French unit began its transition to reconnaissance Mustangs. In January 1945, the Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron 2/33 of the French Air Force took their F-6C’s and F-6D’s over Germany on photographic mapping missions. The Mustangs remained in service until the early 1950’s, when they were replaced by jet fighters.

Nazi Germany

Several P-51s were captured by the Luftwaffe as Beuteflugzeug (captured aircraft) following crash landings. These aircraft were subsequently repaired and test-flown by the Zirkus Rosarius, or Rosarius Staffel, the official Erprobungskommando of the Luftwaffe High Command, for combat evaluation at Göttingen. The aircraft were repainted with German markings and bright yellow nose and belly for identification. A number of P-51B/P-51C’s (including examples marked with Luftwaffe Geschwaderkennung codes T9+CK, T9+FK, T9+HK and T9+PK) and three P-51Ds were captured. Some of these P-51s were found by Allied forces at the end of the war; others crashed during testing. The Mustang Mk.I’s also listed in the appendix to the novel KG 200 as having been flown by the German secret operations unit KG 200, which tested, evaluated and sometimes clandestinely operated captured enemy aircraft during World War II.

Guatemala

The Fuerza Aérea Guatemalteca (FAG) had 30 P-51D Mustangs in service from 1954 to the early 1970s.

Haiti

Haiti had four P-51D Mustangs when President Paul Eugène Magloire was in power between 1950 and 1956, with the last retired in 1973-74 and sold for spares to the Dominican Republic.

Indonesia

Indonesia acquired some P-51Ds from the departing Netherlands East Indies Air Force in 1949 and 1950. The Mustangs were used against Commonwealth (RAF, RAAF and RNZAF) forces during the Indonesian confrontation in the early 1960’s. The last time Mustangs were deployed for military purposes was a shipment of six Cavalier II Mustangs (without tip tanks) delivered to Indonesia in 1972-1973, which were replaced in 1976.

Israel

A few P-51 Mustangs were illegally bought by Israel in 1948, crated and smuggled into the country as agricultural equipment for use in the War of Independence (1948) and quickly established themselves as the best fighter in the Israeli inventory. Further aircraft were bought from Sweden, and were replaced by jets at the end of the 1950’s, but not before the type was used in the Suez Crisis, Operation Kadesh (1956). Reputedly, during this conflict, one daring Israeli pilot literally cut communications between Suez City and the Egyptian front lines by using his Mustang’s propeller on the telephone wires.

Italy

Italy was a postwar operator of P-51Ds; deliveries were slowed by the Korean war, but between September 1947 and January 1951, by MDAP count, 173 examples were delivered. They were used in all the AMI fighter units: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 51 Stormo (Wing), and some in schools and experimental units. Considered a "glamorous" fighter, P-51s were even used as personal aircraft by several Italian commanders. Some restrictions were placed on its use due to unfavorable flying characteristics. Handling had to be done with much care when fuel tanks were fully utilized and several aerobatic maneuvers were forbidden. Overall, the P-51D was highly rated even compared to the other primary postwar fighter in Italian service, the Supermarine Spitfire, partly because these P-51Ds were in very good condition in contrast to all other Allied fighters supplied to Italy. Phasing out of the Mustang began in summer 1958.

Japan

The P-51C-11-NT Evalina, marked as "278" (former USAAF serial: AF 44-10816) and flown by 26th FS, 51st FG, was hit by gunfire on 16 January 1945 and belly-landed on Suchon Airfield in China, which was held by the Japanese. The Japanese repaired the aircraft, roughly applied Hinomaru roundels and flew the aircraft to the Fussa evaluation center (now Yokota Air Base) in Japan.

Netherlands

The Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force received 40 P-51Ds and flew them during the Indonesian National Revolution particularly the two ’politionele acties’: Operatie Product in 1947 and Operatie Kraai in 1949. When the conflict was over, Indonesia received some of the ML-KNIL Mustangs.

Nicaragua

Fuerza Aerea de Nicaragua (GN) purchased 26 P-51D Mustangs from Sweden in 1954 and later received 30 P-51D Mustangs from the U.S. together with two TF-51 models from MAP after 1954. All aircraft of this type were retired from service by 1964.

New Zealand

New Zealand ordered 370 P-51 Mustangs to supplement its F4U Corsairs in the Pacific Ocean Areas theater. Scheduled deliveries were for an initial batch of 30 P-51Ds, followed by 137 more P-51Ds and 203 P-51Ms. The original 30 were being shipped as the war ended in August 1945; these were stored in their packing cases and the order for the additional Mustangs was canceled. In 1951 the stored Mustangs entered service in 1 (Auckland), 2(Wellington), 3 (Canterbury) and 4 (Otago) squadrons of the Territorial Air Force (TAF). The Mustangs remained in service until they were prematurely retired in August 1955 following a series of problems with undercarriage and coolant system corrosion problems. Four Mustangs served on as target tugs until the TAF was disbanded in 1957. RNZAF pilots in the Royal Air Force also flew the P-51, and at least one New Zealand pilot scored victories over Europe while on loan to a USAAF P-51 squadron.

Philippines

The Philippines acquired 103 P-51D Mustangs after World War II. These became the Backbone of the postwar Philippine Army Air Corps and Philippine Air Force and were used extensively during the Huk campaign, fighting against Communist insurgents. The tailwheels were fixed in the extended position. Mustangs were also the first aircraft of the Philippine air demonstration squadron, which was formed in 1953 and given the name "The Blue Diamonds" the following year. The Mustangs were replaced by 56 F-86 Sabres in the late 1950’s, but some were still in service for COIN roles up to the early 1980’s.

Poland

During World War II, five Polish Air Force in Great Britain squadrons used Mustangs. The first Polish unit equipped (7 June 1942) with Mustang Mk.I’s was "B" Flight of 309 "Ziemi Czerwienskiej" Squadron (an Army Co-Operation Command unit), followed by "A" Flight in March 1943. Subsequently, 309 Squadron was redesignated a fighter/reconnaissance unit and became part of Fighter Command. On 13 March 1944, 316 "Warszawski" Squadron received their first Mustang Mk.III’s; rearming of the unit was completed by the end of April. By 26 March 1943, 306 "Torunski" Sqn and 315 "Deblinski" Sqn received Mustangs Mk.III’s (the whole operation took 12 days). On 20 October 1944, Mustang Mk.I’s in No. 309 Squadron were replaced by Mk.IIIs On 11 December 1944, the unit was again renamed, becoming 309 Dywizjon Mysliwski "Ziemi Czerwienskiej" or 309 "Land of Czerwien" Polish Fighter Squadron. In 1945, 303 "Kosciuszko" Sqn received 20 Mustangs Mk.IV/Mk.IVA replacements. Postwar, between 6 December 1946 and 6 January 1947, all five Polish squadrons equipped with Mustangs were disbanded. Poland returned approximately 80 Mustangs Mk.III’s and 20 Mustangs Mk.IV/Mk.IVs to the RAF, which transferred them to the U.S. government.

Somalia

The Somalian Air Force operated eight P-51Ds in post-World War II service.

South Africa

South African Air Force operated a number of Mustang Mk.III’s (P-51B/C) and Mk.IV’s (P-51D/K) in Italy during World War II, beginning in September 1944 when the squadron converted to the Mustang Mk.III from Kittyhawks. The Mk.IV and Mk.IVA came into SA service in March 1945. These aircraft were generally camouflaged in the British style, having been drawn from RAF stocks; all carried RAF serial numbers and were struck off charge and scrapped in October 1945. In 1950, 2 Squadron SAAF was supplied with F-51D Mustangs by the United States for Korean War service. The type performed well in South African hands before being replaced by the F-86 Sabre in 1952 and 1953.

South Korea

Within a month of the outbreak of the Korean War, 10 F-51D Mustangs were provided to the badly depleted Republic of Korea Air Force as a part of the Bout One Project. They were flown by both South Korean airmen, several of whom were veterans of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy air services during World War II, as well as by U.S. advisers led by Major Dean Hess. Later, more were provided both from U.S. and from South African stocks, as the latter were converting to F-86 Sabres. They formed the Backbone of the South Korean Air Force until they were replaced by Sabres. It also served with the ROKAF Black Eagles aerobatic team, until retired 1954.

Sweden

Sweden’s Flygvapnet first recuperated four of the P-51s (two P-51Bs and two early P-51Ds) that had been diverted to Sweden during missions over Europe. In February 1945, Sweden purchased 50 P-51Ds designated J.26, which were delivered by American pilots in April and assigned to the F 16 wing at Uppsala as interceptors. In early 1946, the F 4 wing at östersund was equipped with a second batch of 90 P-51Ds. A final batch of 21 Mustangs was purchased in 1948. In all, 161 J.22s served in the Swedish Air Force during the late 1940’s. About 12 were modified for photo reconnaissance and re-designated S.26. Some of these aircraft participated in the secret Swedish mapping of new Soviet military installations at the Baltic coast in 1946-47 (Operation Falun), an endeavor that entailed many intentional violations of Soviet airspace. However, the Mustang could outdive any Soviet fighter of that era, so no S.22’s were lost in these missions. The J.22s were replaced by De Havilland Vampires around 1950. The S.22’s were replaced by S.29Cs in the early 1950’s.

Switzerland

The Swiss Air Force operated a few USAAF P-51s that had been impounded by Swiss authorities during World War II after the pilots were forced to land in neutral Switzerland. After the war, Switzerland also bought 130 P-51s for $4,000 each. They served until 1958.

United Kingdom

The RAF was the first air force to operate the Mustang. Because the first Mustangs were built to British requirements, these aircraft used factory numbers and were not P-51s; the order comprised 320 NA-73s, followed by 300 NA-83s, all of which were designated North American Mustang Mark I’s by the RAF. The first RAF Mustangs diverted from American orders were 93 P-51s, designated Mark IA, followed by 50 P-51As used as Mustang II’s. The first Mustang Mk.I’s entered service in 1941 the first unit being 2 Squadron RAF. Due to poor high-altitude performance, the Mustangs were used by Army Co-operation Command, rather than Fighter Command, and were used for tactical reconnaissance and ground-attack duties. On 27 July 1942, 16 RAF Mustangs undertook their first long-range reconnaissance mission over Germany. During Operation Jubilee (19 August 1942) four British and Canadian Mustang squadrons, including 26 Squadron saw action. By 1943/1944, British Mustangs were used extensively to seek out V-1 flying bomb sites. The final RAF Mustang Mk.I and Mustang Mk.II aircraft were struck off charge in 1945. The RAF also operated a total of 308 P-51Bs and 636 P-51C’s which were known in RAF service as Mustang Mk.III’s; the first units converted to the type in late 1943 and early 1944. Mustang Mk.III units were operational until the end of World War II, though many units had already converted to the Mustang Mk.IV and Mk.IVs (828 in total, comprising 282 P-51D-NAs or Mk.IV’s, and 600 P-51Ks or Mk.IVA). As the Mustang was a Lend-Lease type, all aircraft still on RAF charge at the end of the war were either returned to the USAAF "on paper" or retained by the RAF for scrapping. The final Mustangs were retired from RAF use in 1947.

USSR

The Soviet Union received at least 10 early-model ex-RAF Mustang I’s and tested but found them to "under-perform" compared to contemporary USSR fighters, relegating them to training units. Later Lend-Lease deliveries of the P-51B/C and D series along with other Mustangs abandoned in Russia after the famous "shuttle missions" were repaired and used by the Soviet Air Force, but not in front-line service.

Uruguay

The Uruguayan Air Force (FAU) used 25 P-51D Mustangs from 1950 to 1960’some were subsequently sold to Bolivia.

P-51s and Civil Aviation

Many P-51s were sold as surplus after the war, often for as little as $1,500. Some were sold to former wartime fliers or other aficionados for personal use, while others were modified for air racing.

One of the most significant Mustangs involved in air racing was a surplus P-51C-10-NT (AF 44-10947) purchased by film stunt pilot Paul Mantz. The aircraft was modified by creating a "wet wing", sealing the wing to create a giant fuel tank in each wing, which eliminated the need for fuel stops or drag-inducing drop tanks. This Mustang, called Blaze of Noon, came in first in the 1946 and 1947 Bendix Air Races, second in the 1948 Bendix, and third in the 1949 Bendix. He also set a U.S. coast-to-coast record in 1947. The Mantz Mustang was sold to Charles F. Blair Jr (future husband of Maureen O’Hara) and renamed Excalibur III. Blair used it to set a New York-to-London (c. 3,460 mi/5,568 km) record in 1951: 7 hrs 48 min from takeoff at Idlewild to overhead London Airport. Later that same year, he flew from Norway to Fairbanks, Alaska, via the North Pole (c. 3,130 mi/5,037 km), proving that navigation via sun sights was possible over the magnetic north pole region. For this feat, he was awarded the Harmon Trophy, and the Air Force was forced to change its thoughts on a possible Soviet air strike from the north. This Mustang now resides in the National Air and Space Museum at Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.

The most prominent firm to convert Mustangs to civilian use was Trans-Florida Aviation, later renamed Cavalier Aircraft Corporation, which produced the Cavalier Mustang. Modifications included a taller tailfin and wingtip tanks. A number of conversions included a Cavalier Mustang specialty: a "tight" second seat added in the space formerly occupied by the military radio and fuselage fuel tank.

In 1958, 78 surviving RCAF Mustangs were retired from service’s inventory and were ferried by Lynn Garrison an RCAF pilot, from their varied storage locations to Canastota, New York where the American buyers were based. In effect, Garrison flew each of the surviving aircraft at least once. These aircraft make up a large percentage of the aircraft presently flying worldwide.

In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, when the United States Department of Defense wished to supply aircraft to South American countries and later Indonesia for close air support and counter insurgency, it turned to Cavalier to return some of their civilian conversions Back to updated military specifications.

In the 21st century a P-51 can command a price of more than $1 million, even for only partially restored aircraft. According to the FAA there are 204 privately owned P-51s in the U.S., most of which are still flying, often associated with organizations such as the Commemorative Air Force (formerly the Confederate Air Force).

On 16 September 2011, The Galloping Ghost, a modified P-51 piloted by Jimmy Leeward of Ocala, Florida, crashed during an air race in Reno, Nevada. Leeward and at least nine people on the ground were killed when the racer suddenly crashed near the edge of the grandstand.

North American P-51 Variants

Mustang Mk.I/P-51/P-51A

The first production contract was awarded by the British for 320 NA-73 fighters, named Mustang Mk.I by an anonymous member of the British Purchasing Commission; a second British contract soon followed, which called for 300 more (NA-83) Mustang Mk.I fighters. Contractual arrangements were also made for two aircraft from the first order to be delivered to the USAAC for evaluation; these two airframes, AF 41-038 and AF 41-039 respectively, were designated XP-51. The first RAF Mustang Mk.I’s were delivered to 2 Squadron and made their combat debut on 10 May 1942. With their long range and excellent low-altitude performance, they were employed effectively for tactical reconnaissance and ground-attack duties over the English Channel, but were thought to be of limited value as fighters due to their poor performance above 15,000 ft (4,600 m).

P-51/Mustang Mk.IA

The first American order for 150 P-51s, designated NA-91 by North American, were placed by the Army on 7 July 1940. The two XP-51s (AF 41-038 and AF 41-039) set aside for testing arrived at Wright Field on 24 August and 16 December 1941 respectively. The relatively small size of this first order reflected the fact that the USAAC was still a relatively small, underfunded peacetime organization. After the attack on Pearl Harbor priority had to be given to building as many of the existing fighters - Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, Bell P-39 Airacobras and Curtiss P-40 Warhawks - as possible while simultaneously training pilots and other personnel, which meant that the evaluation of the XP-51s did not begin immediately. However, this did not mean that the XP-51s were neglected, or their testing and evaluation mishandled. The 150 NA-91s were designated P-51 by the newly formed USAAF and were initially named Apache, although this was soon dropped, and the RAF name, Mustang, adopted instead. The USAAF did not like the mixed armament of the British Mustang Mk.I’s and instead adopted an armament of four long-barrelled 20mm (.79 in) Hispano Mk.II cannon, and deleted the .50 cal engine cowling mounted weapons. The British designated this model as Mustang Mk.IA. A number of aircraft from this lot were fitted out by the USAAF as F-6A photo-reconnaissance aircraft. The British would fit a number of Mustang Mk.I’s with similar equipment.

It was quickly evident that the Mustang’s performance, although exceptional up to 15,000 ft (4,600 m), was markedly reduced at higher altitudes. The single-speed, single-stage supercharger fitted to the Allison V-1710 engine had been designed to produce its maximum power at a low altitude. Above 15,000 feet, the supercharger’s critical altitude rating, the power dropped off rapidly. Prior to the Mustang project, the USAAC had Allison concentrate primarily on turbochargers in concert with General Electric; the turbochargers proved to be reliable and capable of providing significant power increases in the Lockheed P-38 Lightning and other high-altitude aircraft, in particular in the Air Corps’s four-engine bombers. Most of the other uses for the Allison were for low-altitude designs, where a simpler supercharger would suffice. Fitting a turbocharger into the Mustang proved impractical, and Allison was forced to use the only supercharger that was available. In spite of this, the Mustang’s advanced aerodynamics showed to advantage, as the Mustang Mk.I was about 30 mph (48 km/h) faster than contemporary Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters using the same engine (the V-1710-39 producing 1,220 hp (910 kW) at 10,500 ft (3,200 m), driving a 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m) diameter, three-blade Curtiss-Electric propeller). The Mustang Mk.I was 30 mph (48 km/h) faster than the Spitfire Mk.Vc at 5,000 ft (1,500 m) and 35 mph (56 km/h) faster at 15,000 ft (4,600 m), despite the British aircraft’s more powerful engine.

Although it has often been stated that the poor performance of the Allison engine above 15,000 ft (4,600 m) was a surprise and disappointment to the RAF and USAAF, this has to be regarded as a myth; aviation engineers of the time were fully capable of correctly assessing the performance of an aircraft’s engine and supercharger. As evidence of this, in mid-1941, the 93rd and 102nd airframes from the NA-91 order were slated to be set aside and fitted and tested with Packard Merlin engines, with each receiving the designation XP-51B.

P-51A/Mustang Mk.II

On 23 June 1942, a contract was placed for 1,200 P-51As (NA-99s), later reduced to 310 aircraft. The P-51A used the new Allison V-1710-81 engine, a development of the V-1710-39, driving a 10 ft 9 in (3.28 m) diameter three-bladed Curtiss-Electric propeller. The armament was changed to four wing-mounted .50 in (12.7 mm) Browning machine guns, two in each wing, with a maximum of 350 rpg (rpg) for the inboard guns and 280 rpg for the outboard. Other improvements were made in parallel with the North American A-36 Apache, including an improved, fixed air duct inlet replacing the movable fitting of previous Mustang models and the fitting of wing racks able to carry either 75 or 150 U.S. gal (284 or 568 l) drop tanks, increasing the maximum ferry range to 2,740 mi (4,410 km) with the 150 gal (568 l) tanks. The top speed was raised to 409 mph (658 km/h) at 10,000 ft (3,000 m). A total of 50 aircraft were shipped to England, serving as Mustang Mk.II’s in the RAF.

A-36 Apache/Invader

On 16 April 1942, Fighter Project Officer Benjamin S. Kelsey ordered 500 North American A-36 Apaches, a redesign that included six .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns, dive brakes, and the ability to carry two 500 lb (230 kg) bombs. Kelsey would rather have bought more fighters but was willing instead to initiate a higher level of Mustang production at North American by using USAAC funds earmarked for ground-attack aircraft when pursuit aircraft funding had already been allocated.

The 500 were designated A-36A (NA-97). This model became the first USAAF Mustang to see combat. One aircraft (EW998) was passed to the British who gave it the name Mustang Mk.I (Dive Bomber).

Merlin-engine Mustangs

Mustang X

In April 1942, the RAF’s Air Fighting Development Unit (AFDU) tested the Mustang and found its performance inadequate at higher altitudes. As such, it was to be used to replace the Curtiss Tomahawk in Army Cooperation Command squadrons, but the commanding officer was so impressed with its maneuverability and low-altitude speeds that he invited Ronnie Harker from Rolls-Royce’s Flight Test establishment to fly it. Rolls-Royce engineers rapidly realized that equipping the Mustang with a Merlin 61 engine with its two-speed two-stage supercharger would substantially improve performance and started converting five aircraft as the Mustang Mk X. Apart from the engine installation, which utilized custom-built engine bearers designed by Rolls-Royce and a standard 10 ft 9 in (3.28 m) diameter, four-bladed Rotol propeller from a Spitfire Mk.IX, the Mustang Mk.X was a straightforward adaptation of the Mustang Mk.I airframe, keeping the same radiator duct design. The Vice-Chief of the Air Staff, Air Marshal Sir Wilfrid R. Freeman, lobbied vociferously for Merlin-powered Mustangs, insisting two of the five experimental Mustang Mk.Xs be handed over to Carl Spaatz for trials and evaluation by the U.S. 8th Air Force in Britain. The high-altitude performance improvement was remarkable: the Mustang Mk.X (serial number AM208) reached 433 mph (697 km/h) at 22,000 ft (6,700 m), and AL975 tested at an absolute ceiling of 40,600 ft (12,400 m).

P-51B and P-51C

The two XP-51Bs were a more thorough conversion than the Mustang Mk.X, with a tailor-made engine installation and a complete redesign of the radiator duct. The airframe itself was strengthened, with the fuselage and engine mount area receiving more formers because of the greater weight of the Packard V-1650-3, 1,690 lb (770 kg), compared with the Allison V-1710s 1,335 lb (606 kg). The engine cowling was completely redesigned to house the Packard Merlin, which, because of the intercooler radiator mounted on the supercharger casing, was 5 in (130 mm) taller and used an updraught induction system, rather than the downdraught carburetor of the Allison. The new engine drove a four-bladed 11 ft 2 in (3.40 m) diameter Hamilton Standard propeller that featured cuffs of hard molded rubber. To cater for the increased cooling requirements of the Merlin a new fuselage duct was designed. This housed a larger radiator, which incorporated a section for the supercharger coolant, and, forward of this and slightly lower, an oil cooler was housed in a secondary duct which drew air through the main opening and exhausted via a separate exit flap.

A "duct rumble" heard by pilots in flight in the prototype P-51B resulted in a full-scale wind-tunnel test at NACA Ames Aeronautical Laboratory. This was carried out by inserting the airplane, with the outer wing panels removed, into the 16-foot wind tunnel. A test engineer would sit in the cockpit with the wind tunnel running and listen for the duct rumble. It was eventually found that the rumble could be eliminated by increasing the gap between the lower surface of the wing and the lip of the cooling system duct from 1 inch to 2 inches. The conclusion was that part of the boundary layer on the lower surface of the wing was being ingested into the inlet and separating, causing the radiator to vibrate and producing the rumble. The inlet that went into production on the P-51B was lowered even further to give a separation of 2.63 inches from the bottom of the wing. In addition, the shelf that extended above the oil cooler face was removed and the inlet highlight was swept Back.

It was decided that new P-51B (NA-102) would continue with the four wing-mounted .50 in (12.7 mm) M2/AN Browning machine guns (with 350 rpg for the inboard guns and 280 rpg for the outboard) first used in the P-51A, while the bomb rack/external drop tank installation was adapted from the A-36 Apache; the racks were rated to be able to carry up to 500 lb (230 kg) of ordnance and were also capable of carrying drop tanks. The weapons were aimed using the electrically illuminated N-3B reflector sight fitted with an A-1 head assembly which allowed it to be used as a gun or bomb sight through varying the angle of the reflector glass. Pilots were also given the option of having ring and bead sights mounted on the top engine cowling formers. This option was discontinued with the later P-51Ds.

The first XP-51B flew on 30 November 1942. Flight tests confirmed the potential of the new fighter, with the service ceiling being raised by 10,000 feet, with the top speed improving by 50 mph at 30,000 ft (9,100 m). American production was started in early 1943 with the P-51B (NA-102) being manufactured at Inglewood, CA, and the P-51C (NA-103) at a new plant in Dallas, Texas, which was in operation by summer 1943. The RAF named these models Mustang Mk.III. In performance tests, the P-51B reached 441 mph (709.70 km/h) at 30,000 ft (9,100 m). In addition, the extended range made possible by the use of drop tanks enabled the Merlin-powered Mustang to be introduced as a bomber escort with a combat radius of 750 miles using two 75 gal tanks.

The range would be further increased with the introduction of an 85 gal (322 liter) self-sealing fuel tank aft of the pilot’s seat, starting with the P-51B-5-NA series. When this tank was full, the center of gravity of the Mustang was moved dangerously close to the aft limit. As a result, maneuvers were restricted until the tank was down to about 25 U.S. gal (95 liters) and the external tanks had been dropped. Problems with high-speed "porpoising" of the P-51Bs and P-51C’s with the fuselage tanks would lead to the replacement of the fabric-covered elevators with metal-covered surfaces and a reduction of the tailplane incidence. With the fuselage and wing tanks, plus two 75 gal drop tanks, the combat radius was now 880 miles.

Despite these modifications, the P-51Bs and P-51C’s, and the newer P-51Ds and P-51Ks, experienced low-speed handling problems that could result in an involuntary "snap-roll" under certain conditions of air speed, angle of attack, gross weight, and center of gravity. Several crash reports tell of P-51Bs and P-51C’s crashing because horizontal stabilizers were torn off during maneuvering. As a result of these problems, a modification kit consisting of a dorsal fin was manufactured. One report stated:

"Unless a dorsal fin is installed on the P-51B, P-51C and P-51D airplanes, a snap roll may result when attempting a slow roll. The horizontal stabilizer will not withstand the effects of a snap roll. To prevent recurrence, the stabilizer should be reinforced in accordance with T.O. 01-60J-18 dated 8 April 1944 and a dorsal fin should be installed. Dorsal fin kits are being made available to overseas activities."

The dorsal fin kits became available in August 1944, and were fitted to P-51Bs and P-51C’s, and to P-51Ds and P-51Ks. Also incorporated was a change to the rudder trim tabs, which would help prevent the pilot over-controlling the aircraft and creating heavy loads on the tail unit.

One of the few remaining complaints with the Merlin-powered aircraft was a poor rearward view. The canopy structure, which was the same as the Allison-engine Mustangs, was made up of flat, framed panels; the pilot gained access, or exited the cockpit by lowering the portside panel and raising the top panel to the right. The canopy could not be opened in flight and tall pilots especially, were hampered by limited headroom. In order to at least partially improve the view from the Mustang, the British had field-modified some Mustangs with clear, sliding canopies called Malcolm hoods (designed by Robert Malcolm), and whose design had also been adopted by the U.S. Navy’s own Chance-Vought F4U-1D version of the Corsair in April 1944.

The new structure was a frameless Plexiglas moulding which ballooned outwards at the top and sides, increasing the headroom and allowing increased visibility to the sides and rear. Because the new structure slid Backwards on runners it could be slid open in flight. The aerial mast behind the canopy was replaced by a "whip" aerial which was mounted further aft and offset to the right. Most British Mk.III’s were equipped with Malcolm hoods. Several American service groups "acquired" the necessary conversion kits and some American P-51B/P-51C’s appeared with the new canopy, although the majority continued to use the original framed canopies.

P-51Bs and P-51C’s started to arrive in England in August and October 1943. The P-51B/P-51C versions were sent to 15 fighter groups that were part of the 8th and 9th Air Forces in England and the 12th and 15th in Italy (the southern part of Italy was under Allied control by late 1943). Other deployments included the China Burma India Theater (CBI).

Allied strategists quickly exploited the long-range fighter as a bomber escort. It was largely due to the P-51 that daylight bombing raids deep into German territory became possible without prohibitive bomber losses in late 1943.

A number of the P-51B and P-51C aircraft were fitted for photo reconnaissance and designated F-6C.

P-51D and P-51K

Following combat experience the P-51D series introduced a "teardrop", or "bubble", canopy to rectify problems with poor visibility to the rear of the aircraft. In America new moulding techniques had been developed to form streamlined nose transparencies for bombers. North American designed a new streamlined plexiglass canopy for the P-51B which was later developed into the teardrop shaped bubble canopy. In late 1942 the tenth production P-51B-1-NA was removed from the assembly lines. From the windshield aft the fuselage was redesigned by cutting down the rear fuselage formers to the same height as those forward of the cockpit; the new shape faired in to the vertical tail unit. A new simpler style of windscreen, with an angled bullet-resistant windscreen mounted on two flat side pieces improved the forward view while the new canopy resulted in exceptional all-round visibility. Wind tunnel tests of a wooden model confirmed that the aerodynamics were sound.

The new model Mustang also had a redesigned wing; alterations to the undercarriage up-locks and inner-door retracting mechanisms meant that there was an additional fillet added forward of each of the wheel bays, increasing the wing area and creating a distinctive "kink" to the leading edges of the inner wings.

Other alterations to the wings included new navigation lights, mounted on the wingtips, rather than the smaller lights above and below the wings of the earlier Mustangs, and retractable landing lights which were mounted at the Back of the wheel wells; these replaced the lights which had been formally mounted in the wing leading edges.

The armament was increased with the addition of two more .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns, bringing the total to six. The inner pair of machine guns had 400 rpg, and the others had 270 rpg, for a total of 1,880. In previous P-51s, the M2s were mounted at large angle to allow access to the feed chutes from the ammunition trays. This angled mounting had caused problems with the ammunition feed and with spent casings and links failing to clear the gun-chutes, leading to frequent complaints that the guns jammed during combat maneuvers. The new arrangement allowed the M2s to be mounted upright, remedying most of the jamming problems. In addition the weapons were installed along the line of the wing’s dihedral, rather than parallel to the ground line as in the earlier Mustangs.

The wing racks fitted to the P-51D/P-51K series were strengthened and were able to carry up to 1,000 lb (450 kg) of ordnance, although 500 lb (230 kg) bombs were the recommended maximum load. Later models had removable under-wing ’Zero Rail’ rocket pylons added to carry up to ten T64 5.0 in (127 mm) H.V.A.R rockets per plane. The gun sight was changed from the N-3B to the N-9 before the introduction in September 1944 of the K-14 or K-14A gyro-computing sight. Apart from these changes, the P-51D and P-51K series retained V-1650-7 engine used in the majority of the P-51B/C series.

The addition of the 85 U.S gallon (322 liter) fuselage fuel tank, coupled with the reduction in area of the new rear fuselage, exacerbated the handling problems already experienced with the P-51B/C series when fitted with the tank, and led to a fillet being added to the base of the vertical tailfin. P-51Ds without fuselage fuel tanks were fitted with either the SCR-522-A or SCR-274-N Command Radio sets and SCR-695-A, or SCR-515 radio transmitters, as well as an AN/APS-13 rear-warning set; P-51Ds and P-51Ks with fuselage tanks used the SCR-522-A and AN/APS-13 only.

The P-51D became the most widely produced variant of the Mustang. During 1945-48, P-51Ds were also built under licence in Australia by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation. A Dallas-built version of the P-51D, designated the P-51K, was equipped with an 11 ft (3.4 m) diameter Aeroproducts propeller in place of the 11.2 ft (3.4 m) Hamilton Standard propeller. The hollow-bladed Aeroproducts propeller was unreliable, due to manufacturing problems, with dangerous vibrations at full throttle and was eventually replaced by the Hamilton Standard. By the time of the Korean War, most F-51s were equipped with "uncuffed" Hamilton Standard propellers with wider, blunt-tipped blades.

The photo reconnaissance versions of the P-51D and P-51K were designated F-6D and F-6K respectively. The RAF assigned the name Mustang Mk.IV to the P-51D model and Mustang Mk.IVA to P-51K models.

The P-51D/P-51K started arriving in Europe in mid-1944 and quickly became the primary USAAF fighter in the theater. It was produced in larger numbers than any other Mustang variant. Nevertheless, by the end of the war, roughly half of all operational Mustangs were still P-51B or P-51C models.

The "Lightweight" Mustangs - XP-51F, XP-51G and XP-51J

The USAAF required airframes built to their acceleration standard of 8.33g (82 m/s2), a higher load factor than that used by the British standard of 5.33g (52 m/s2) for their fighters. Reducing the load factor to 5.33 would allow weight to be removed, and both the USAAF and the RAF were interested in the potential performance boost. The lightweight Mustangs also had an all-new wing design. The wing airfoils were switched to the NACA 66,2-(1.8)15.5 a=.6 at the root and the NACA 66,2-(1.8)12 a=.6 at the tip. These airfoils were designed to give more low-drag laminar flow than the previous NAA/NACA 45-100 airfoils. In addition, the wing planform was a simple trapezoid, with no leading extension in the wing root region.In 1943, North American submitted a proposal to redesign the P-51D as model NA-105, which was accepted by the USAAF. Modifications included changes to the cowling, a simplified undercarriage with smaller wheels and disc brakes, and a larger canopy and an armament of four .50 Brownings. In total the design was some 1,600 pounds lighter than the P-51D. In test flights the XP-51F achieved 491 mph (790 km/h) at 21,000 feet. The designation XP-51F was assigned to prototypes powered with V-1650 engines (a small number of XP-51F’s were passed to the British as the Mustang V), and XP-51G to those with reverse lend/lease Merlin RM 14 SM engines.

A third lightweight prototype powered by an Allison V-1710-119 engine was added to the development program. This aircraft was designated XP-51J. Since the engine was insufficiently developed, the XP-51J was loaned to Allison for engine development. None of these experimental lightweights went into production.

P-51H

The P-51H (NA-126) was the final production Mustang, embodying the experience gained in the development of the XP-51F and XP-51G aircraft. This aircraft, with minor differences as the NA-129, came too late to participate in World War II, but it brought the development of the Mustang to a peak as one of the fastest production piston-engine fighters to see service.

The P-51H used the new V-1650-9 engine, a version of the Merlin that included Simmons automatic supercharger boost control with water injection, allowing War Emergency Power as high as 2,218 hp (1,500 kW). Differences between the P-51D included lengthening the fuselage and increasing the height of the tailfin, which greatly reduced the tendency to yaw. The canopy resembled the P-51D style, over a raised pilot’s position. Service access to the guns and ammunition was also improved. With the new airframe several hundred pounds lighter, the extra power and a more streamlined radiator, the P-51H was among the fastest propeller fighters ever, able to reach 487 mph (784 km/h or Mach 0.74) at 25,000 ft (7,600 m).

The North American P-51H Mustang was designed to complement the Republic P-47N Thunderbolt as the primary aircraft for the invasion of Japan, with 2,000 ordered to be manufactured at Inglewood. Production was just ramping up with 555 delivered when the war ended.

Additional orders, already on the books, were canceled. With the cutback in production, the variants of the P-51H with different versions of the Merlin engine were produced in either limited numbers or terminated. These included the P-51L, similar to the P-51H but utilizing the 2,270 hp (1,690 kW) V-1650-11 engine, which was never built; and its Dallas-built version, the P-51M, or NA-124, which utilized the V-1650-9A engine lacking water injection and therefore rated for lower maximum power, of which one was built out of the original 1,629 ordered (AF 45-11743).

Although some P-51H’s were issued to operational units, none saw combat in World War II, and in postwar service, most were issued to reserve units. One aircraft was provided to the RAF for testing and evaluation. AF 44-64192 was designated BuNo 09064 and used by the U.S. Navy to test transonic airfoil designs and then returned to the Air National Guard in 1952. The P-51H was not used for combat in the Korean War despite its improved handling characteristics, since the P-51D was available in much larger numbers and was a proven commodity.

Many of the aerodynamic advances of the P-51 (including the laminar flow wing) were carried over to North American’s next generation of jet-powered fighters, the Navy FJ Fury and Air Force F-86 Sabre. The wings, empennage and canopy of the first straight-winged variant of the Fury (FJ-1) and the unbuilt preliminary prototypes of the P-86/F-86 strongly resembled those of the Mustang before the aircraft were modified with swept-wing designs.

Experimental Mustangs

In early 1944, the first P-51A-1-NA (AF 43-6003) was fitted and tested with a lightweight retractable ski kit replacing the wheels. This conversion was made in response to a perceived requirement for aircraft that would operate away from prepared airstrips. The main oleo leg fairings were retained, but the main wheel doors and tail wheel doors were removed for the tests. When the undercarriage was retracted, the main gear skis were housed in the space in the lower engine compartment made available by the removal of the fuselage .50 in (12.7 mm) Brownings from the P-51As. The entire installation added 390 lb (180 kg) to the aircraft weight and required that the operating pressure of the hydraulic system had to be increased from 1,000 psi (6,897 kPa) to 1,200 psi (8,276 kPa). Flight tests showed that ground handling was good, and the Mustang could take off and land in a field length of 1,000 ft (300 m); the maximum speed was 18 mph (29 km/h) lower, although it was thought that fairings over the retracted skis would compensate.

Concern over the USAAF’s inability to escort Boeing B-29s all the way to mainland Japan resulted in the highly classified "Seahorse" project (NA-133), an effort to "navalize" the P-51. On 15 November 1944, naval aviator (and later test pilot) Lieutenant Bob Elder, in a P-51D-5-NA (AF 44-14017), started flight tests from the deck of the carrier Shangri-La. This Mustang had been fitted with an arrestor hook, which was attached to a reinforced bulkhead behind the tail wheel opening; the hook was housed in a streamlined position under the rudder fairing and could be released from the cockpit. The tests showed that the Mustang could be flown off the carrier deck without the aid of a catapult, using a flap setting of 20° down and 5° of up elevator. Landings were found to be easy, and, by allowing the tail wheel to contact the deck before the main gear, the aircraft could be stopped in a minimum distance. The project was canceled after U.S. Marines secured the Japanese island of Iwo Jima and its airfields, making it possible for standard P-51D models to accompany B-29s all the way to the Japanese home islands and Back.

While North American were concentrating on improving the performance of the P-51 through the development of the lightweight Mustangs, in Britain, other avenues of development were being pursued. To this end, two Mustang Mk.III’s (P-51Bs and P-51C’s), FX858 and FX901, were fitted with different Merlin engine variants. The first of these, FX858, was fitted with a Merlin 100 by Rolls-Royce at Hucknall; this engine was similar to the RM 14 SM fitted to the XP-51G and was capable of generating 2,080 hp (1,550 kW) at 22,800 ft (7,000 m) using a boost pressure of +25 lbf/in2 (170 kPa; 80 in Hg) in war emergency setting. With this engine, FX858 reached a maximum speed of 453 mph (729 km/h) at 18,000 ft (5,500 m), and this could be maintained to 25,000 ft (7,600 m). The climb rate was 4,160 ft/min (21.1 m/s) at 14,000 ft (4,300 m).

FX901 was fitted with a Merlin 113 (also used in the de Havilland Mosquito B. Mk 35). This engine was similar to the Merlin 100, but it was fitted with a supercharger rated for higher altitudes. FX901 was capable of 454 mph (730 km/h) at 30,000 ft (9,100 m) and 414 mph (666 km/h) at 40,000 ft (12,200 m).

Summary of P-51 Variants

North American P-51D Mustang/ RAF Mustang IV Specifications

Type

Wings

Fuselage

Tail Unit

Landing Gear

Power Plant

Accommodation

Armament

Dimensions

Weights

Performance (Packard V-1650-7 engine)

References