| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

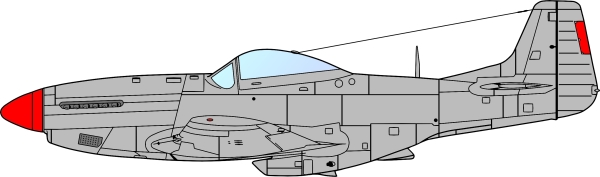

North American P-51D Mustang (NA-124)

WWII single-engine single-seat long-range monoplane escort fighter

Archive Photos ¹

North American P-51D-25-NT Mustang (Su Su) (NA-124, AF 44-84850, c/n 124-44706, N514NH) on display (1/11/2009) at the 2009 Cable Air Show, Cable Airport, Upland, California (Photo by John Shupek)

North American P-51D-25-NT Mustang (Wee Willy II) (NA-124, AF-44-84961 as 44-13334, c/n 124-44817, NL7715C) on display (8/27/2003) at the Planes of Fame Air Museum, Chino, California (Photo by John Shupek)

North American P-51D-25-NT Mustang (Wee Willy II) (NA-124, AF-44-84961 as 44-13334, c/n 124-44817, NL7715C) on display (8/04/2004) at the Planes of Fame Air Museum, Chino, California (Photo by John Shupek)

North American P-51D-25-NT Mustang (Wee Willy II) (NA-124, AF-44-84961 as 44-13334, c/n 124-44817, NL7715C) on display (1/6/2007) at the Planes of Fame Air Museum, Chino, California (Photo by John Shupek)

North American P-51D-25-NT Mustang (Val-Hala) (NA-124, AF 45-11525, c/n 124-48278, N151AF) on display (c.1998) at the Mojave Airport, Mojave, California (Photo by John Shupek)

North American P-51D-30-NT Mustang (NA-124, AF 45-11553, c/n 124-48306, N5415V/511533/FF-553) on display (4/4/1988) at the MCAS El Toro Air Show 1988, MCAS El Toro, California (Photo by John Shupek)

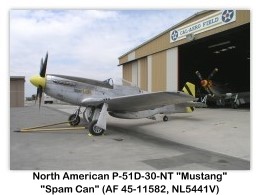

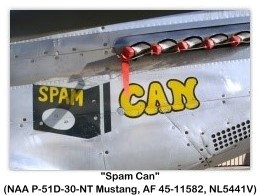

North American P-51D-30-NT Mustang (Spam Can) (NA-124, AF 45-11582, c/n 124-48335, NL5441V) on display (8/27/2003) at the Planes of Fame Air Museum, Chino, California (Photo by John Shupek)

North American P-51D-30-NT Mustang (Spam Can) (NA-124, AF 45-11582, c/n 124-48335, NL5441V) on display (8/4/2004) at the Planes of Fame Air Museum, Chino, California (Photo by John Shupek)

North American P-51D-30-NT Mustang (Spam Can) (NA-124, AF 45-11582, c/n 124-48335, NL5441V) on display (1/6/2007) at the Planes of Fame Air Museum, Chino, California (Photo by John Shupek)

Overview

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang was an American long-range, single-seat fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II, the Korean War and several other conflicts. During World War II, Mustang pilots claimed 4,950 enemy aircraft shot down.

It was conceived, designed and built by North American Aviation (NAA), under the direction of lead engineer Edgar Schmued, in response to a specification issued directly to NAA by the British Purchasing Commission; the prototype NA-73X airframe was rolled out on 9 September 1940, albeit without an engine, 102 days after the contract was signed and first flew on 26 October.

The Mustang was originally designed to use the Allison V-1710 engine, which had limited high-altitude performance. It was first flown operationally by the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a tactical-reconnaissance aircraft and fighter-bomber. The addition of the Rolls-Royce Merlin to the P-51B/C model transformed the Mustang’s performance at altitudes above 15,000 ft, giving it a performance that matched or bettered the majority of the Luftwaffe’s fighters at altitude. The definitive version, the P-51D, was powered by the Packard V-1650-7, a license-built version of the Rolls-Royce Merlin 60 series two-stage two-speed supercharged engine, and armed with six 0.50 caliber (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns.

From late 1943, P-51Bs (supplemented by P-51Ds from mid-1944) were used by the USAAF’s Eighth Air Force to escort bombers in raids over Germany, while the RAF’s 2 TAF and the USAAF’s Ninth Air Force used the Merlin-powered Mustangs as fighter-bombers, roles in which the Mustang helped ensure Allied air superiority in 1944. The P-51 was also in service with Allied air forces in the North African, Mediterranean and Italian theaters, and saw limited service against the Japanese in the Pacific War.

At the start of Korean War, the Mustang was the main fighter of the United Nations until jet fighters such as the F-86 took over this role; the Mustang then became a specialized fighter-bomber. Despite the advent of jet fighters, the Mustang remained in service with some air forces until the early 1980s. After World War II and the Korean War, many Mustangs were converted for civilian use, especially air racing.

Design and Development

Genesis

In April 1938, shortly after the German Anschluss of Austria, the British government established a purchasing commission in the United States, headed by Sir Henry Self. Self was given overall responsibility for Royal Air Force (RAF) production and research and development, and also served with Sir Wilfrid Freeman, the "Air Member for Development and Production". Self also sat on the British Air Council Sub-committee on Supply (or "Supply Committee") and one of his tasks was to organize the manufacturing and supply of American fighter aircraft for the RAF. At the time, the choice was very limited, as no U.S. aircraft then in production or flying met European standards, with only the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk coming close. The Curtiss-Wright plant was running at capacity, so P-40’s were in short supply.

North American Aviation (NAA) was already supplying its Harvard trainer to the RAF, but was otherwise under utilized. NAA President "Dutch" Kindelberger approached Self to sell a new medium bomber, the B-25 Mitchell. Instead, Self asked if NAA could manufacture the Tomahawk under license from Curtiss. Kindelberger said NAA could have a better aircraft with the same engine in the air sooner than establishing a production line for the Curtiss P-40. The Commission stipulated armament of four 0.303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns, the Allison V-1710 liquid-cooled engine, a unit cost of no more than $40,000, and delivery of the first production aircraft by January 1941. In March 1940, 320 aircraft were ordered by Sir Wilfred Freeman who had become the executive head of Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), and the contract was promulgated on 24 April.

The design, known as the NA-73X, followed the best conventional practice of the era, but included several new features. One was a wing designed using laminar flow airfoils which were developed co-operatively by North American Aviation and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). These airfoils generated very low drag at high speeds. During the development of the NA-73X, a wind tunnel test of two wings, one using NACA 5-digit airfoils and the other using the new NAA/NACA 45-100 airfoils, was performed in the University of Washington Kirsten Wind Tunnel. The results of this test showed the superiority of the wing designed with the NAA/NACA 45-100 airfoils. The other feature was a new radiator design that exploited the "Meredith Effect", in which heated air exited the radiator as a slight amount of jet thrust. Because NAA lacked a suitable wind tunnel to test this feature, it used the GALCIT 10 ft (3.0 m) wind tunnel at Caltech. This led to some controversy over whether the Mustang’s cooling system aerodynamics were developed by NAA’s engineer Edgar Schmued or by Curtiss, although NAA had purchased the complete set of Curtiss P-40 and Curtiss XP-46 wind tunnel data and flight test reports for US$56,000. The NA-73X was also one of the first aircraft to have a fuselage lofted mathematically using conic sections; this resulted in the aircraft’s fuselage having smooth, low drag surfaces. To aid production, the airframe was divided into five main sections’forward, center, rear fuselage and two wing halves’all of which were fitted with wiring and piping before being joined.

The prototype NA-73X was rolled out in September 1940 and first flew on 26 October 1940, respectively 102 and 149 days after the order had been placed, an uncommonly short gestation period. The prototype handled well and accommodated an impressive fuel load. The aircraft’s two-section, semi-monocoque fuselage was constructed entirely of aluminum to save weight. It was armed with four 0.30 in (7.62 mm) M1919 Browning machine guns, two in the wings and two mounted under the engine and firing through the propeller arc using gun synchronizing gear.

While the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) could block any sales it considered detrimental to the interests of the US, the NA-73 was considered to be a special case because it had been designed at the behest of the British. In September 1940 a further 300 NA-73s were ordered by MAP. To ensure uninterrupted delivery Colonel Oliver P. Echols arranged with the Anglo-French Purchasing Commission to deliver the aircraft, and NAA gave two examples to the USAAC for evaluation.

Operational History

U.S. Operational Service

Pre-war Theory

Pre-war doctrine of most bomber forces was to attack at night when the bombers would be effectively immune to interception. The loss in accuracy due to limited visibility was a high price to pay, protecting small targets from attack. The only targets that could be attacked were large ones, effectively whole cities. As "the bomber will always get through", the future of war was believed to consist of large fleets of bombers pounding each other’s cities night after night. The Royal Air Force based its development policy on this concept, developing a series of dedicated night bombers.

There were those that dismissed this concept as immoral and continued to press for precision attacks on strategic targets as the most effective means of waging war. The RAF did attempt several long-range daylight raids early in the war using the Vickers Wellington, but suffered such high casualties that they abandoned the effort quickly. The Luftwaffe had the advantage of bases in France that allowed their fighters to escort the bombers at least part way on their missions. This strategy proved ineffective, as the RAF fighters ignored the escorts and attacked the bombers. The Germans abandoned day bombing and switched to night bombing during The Blitz of 1940-41. By the end of 1940, it appeared that daylight strategic bombing was ineffective.

American pre-war doctrine developed out of an isolationist policy that was primarily defensive. The B-17 had originally been designed to attack shipping at long range from U.S. bases. For this role it needed to be able to attack in daylight and used the advanced Norden bombsight to improve accuracy. As the bomber developed, more and more defensive armament was added to outgun the fighters it would face. In light of this heavy defensive firepower, the USAAC came to believe that tightly packed formations of B-17s would have so much firepower that they could fend off fighters on their own. In spite of evidence to the contrary from the RAF and Luftwaffe, this strategy was believed to be sound. When the U.S. entered the war they put this strategy into force, building up a strategic bomber force based in Britain.

Trial by Fire

The 8th Air Force started operations from Britain in August 1942. At first, because of the limited scale of operations, there was no conclusive evidence that the American doctrine was failing. In the 26 operations which had been flown to the end of 1942 the loss rate had been under 2%. This rate was better than the RAF’s night efforts, and similar to the losses one would expect due to mechanical failure.

In January 1943, at the Casablanca Conference, the Allies formulated the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) plan for "round-the-clock" bombing by the RAF at night and the USAAF by day. In June 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued the Pointblank Directive to destroy the Luftwaffe before the invasion of Europe, putting the CBO into full implementation. Following this, the 8th Air Force’s heavy bombers conducted a series of deep-penetration raids into Germany, beyond the range of escort fighters.

German daytime fighter efforts were, at that time, focused on the eastern front and several other distant locations. Initial efforts by the 8th met limited and unorganized resistance, but with every mission the Luftwaffe moved more aircraft to the west and quickly improved their battle direction. The Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission in August lost 60 B-17s of a force of 376, the October 14 attack lost 77 of a force of 291, 26% of the attacking force. Losses were so severe that long-range missions were called off.

The solution was understood - escorting fighters could break up attacks by fighters before they could reach the bombers. The Lockheed P-38 Lightning had the range to escort the bombers, but was only available in small numbers in the European theater due to its Allison engines proving difficult to maintain. It was also a very expensive aircraft to build and operate. The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt was capable of meeting the Luftwaffe on more than even terms, but did not at the time have sufficient range. The Luftwaffe quickly identified its maximum range, and their fighters waited for the bombers just beyond the point where the Thunderbolts had to turn Back.

P-51 Introduction

The P-51 Mustang was a solution to the clear need for an effective bomber escort. The Mustang was at least as simple as other aircraft of its era. It used a common, reliable engine and had internal space for a huge fuel load. With external fuel tanks, it could accompany the bombers all the way to Germany and Back. Enough P-51s became available to the 8th and 9th Air Forces in the winter of 1943-44. When the Pointblank offensive resumed in early 1944, matters changed dramatically. The P-51 proved perfect for escorting bombers all the way to the deepest targets. The Eighth Air Force began to switch its fighter groups to the Mustang, first exchanging arriving P-47 groups for those of the 9th Air Force using P-51s, then gradually converting its Thunderbolt and Lightning groups. The defense was initially layered, using the shorter range P-38s and P-47’s to escort the bombers during the initial stages of the raid and then handing over to the P-51 when they turned for home. By the end of 1944, 14 of its 15 groups flew the Mustang.

The Luftwaffe initially adapted to the U.S. fighters by modifying their tactics, massing in front of the bombers and then attacking in a pass through the formation. Flying in close formation with the bombers, the P-51s had little time to react before the attackers were already running out of range. To better deal with the bombers, the Luftwaffe started increasing the armament on their fighters with heavy cannons. The additional weight decreased performance to the point where their aircraft were vulnerable if caught by the P-51s. At first, their defensive tactic was to avoid prolonged dogfights.

Destroying the Luftwaffe

General James Doolittle told the fighters in early 1944 to stop flying in formation with the bombers and instead attack the Luftwaffe wherever it could be found. The Mustang groups were sent in before the bombers, forming up well ahead of the bomber formations in an air superiority "fighter sweep" manner, and could hunt the German fighters while they were forming up. The results were astonishing; the Luftwaffe lost 17% of its fighter pilots in just over a week. As Doolittle later noted, "Adolf Galland said that the day we took our fighters off the bombers and put them against the German fighters, that is, went from defensive to offensive, Germany lost the air war."

The Luftwaffe answer was the Gefechtsverband (battle formation). It consisted of a Sturmgruppe of heavily armed and armored Fw.190s escorted by two Begleitgruppen of light fighters, often Bf.109s, whose task was to keep the Mustangs away from the Fw.190s attacking the bombers. This scheme was excellent in theory but difficult to apply in practice. The large German formation took a long time to assemble and was difficult to maneuver. It was often intercepted by the escorting P-51s using the newer "fighter sweep" tactics out ahead of the heavy bomber formations, breaking up the Gefechtsverband formations before reaching the bombers; when the Sturmgruppe worked, the effects were devastating. With their engines and cockpits heavily armored, the Fw.190s attacked from astern and gun camera films show that these attacks were often pressed to within 100 yds (90 m).

While not always able to avoid contact with the escorts, the threat of mass attacks and later the "company front" (eight abreast) assaults by armored Sturmgruppe Fw.190s brought an urgency to attacking the Luftwaffe wherever it could be found. Beginning in late February 1944, 8th Air Force fighter units began systematic strafing attacks on German airfields with increasing frequency and intensity throughout the spring with the objective of gaining air supremacy over the Normandy battlefield. In general these were conducted by units returning from escort missions but, beginning in March, many groups also were assigned airfield attacks instead of bomber support. The P-51, particularly with the advent of the K-14 Gyro gun sight and the development of "Clobber Colleges" for the training of fighter pilots in fall 1944, was a decisive element in Allied countermeasures against the Jagdverbände.

The numerical superiority of the USAAF fighters, superb flying characteristics of the P-51, and pilot proficiency helped cripple the Luftwaffe’s fighter force. As a result the fighter threat to US, and later British, bombers was greatly diminished by July 1944. Reichmarshal Hermann Göring, commander of the German Luftwaffe during the war, was quoted as saying, "When I saw Mustangs over Berlin, I knew the jig was up."

Mopping Up

On 15 April 1944, VIII FC began Operation Jackpot, attacks on Luftwaffe fighter airfields. As the efficacy of these missions increased, the number of fighters at the German air bases fell to the point where they were no longer useful targets and on 21 May, targets were expanded to include railways, locomotives and rolling stock used by the Germans to transport materiel and troops, in missions dubbed "Chattanooga". The P-51 excelled at this mission, although losses were much higher on strafing missions than in air-to-air combat, partially because like other fighters using liquid-cooled engines, the Mustang’s coolant system could be punctured by small arms.

Given the overwhelming Allied air superiority, the Luftwaffe put its effort into the development of aircraft of such high performance that they could operate with impunity. Foremost among these were the Messerschmitt Me.163 Komet rocket interceptors and Messerschmitt Me.262 jet fighter. In action, the Me.163 proved to be more dangerous to the Luftwaffe than to the Allies and was never a serious threat. The Me.262 was, but attacks on their airfields neutralized them. The jet engines of the Me.262s needed careful nursing by their pilots and these aircraft were particularly vulnerable during takeoff and landing. Lt. Chuck Yeager of the 357th Fighter Group was one of the first American pilots to shoot down a Me.262 which he caught during its landing approach. On 7 October 1944, Lt. Urban Drew of the 365th Fighter Group shot down two Me.262s that were taking off, while on the same day Lt. Col. Hubert Zemke, who had transferred to the Mustang equipped 479th Fighter Group, shot down what he thought was a Bf.109, only to have his gun camera film reveal that it may have been an Me.262.

The Mustang also proved useful against the V-1’s launched toward London. P-51B/Cs using 150 octane fuel were fast enough to catch the V-1 and operated in concert with shorter-range aircraft like advanced marks of the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Tempest.

By 8 May 1945, the 8th, 9th and 15th Air Force’s P-51 groups claimed some 4,950 aircraft shot down (about half of all USAAF claims in the European theater), the most claimed by any Allied fighter in air-to-air combat and 4,131 destroyed on the ground. Losses were about 2,520 aircraft. The 8th Air Force’s 4th Fighter Group was the top-scoring fighter group in Europe, with 1,016 enemy aircraft claimed destroyed. This included 550 claimed in aerial combat and 466 on the ground.

In air combat, the top-scoring P-51 units (both of which exclusively flew Mustangs) were the 357th Fighter Group of the 8th Air Force with 565 air-to-air combat victories and the Ninth Air Force’s 354th Fighter Group with 664, which made it one of the top scoring fighter groups. Martin Bowman reports that in the European Theater of Operations, Mustangs flew 213,873 sorties and lost 2,520 aircraft to all causes. The top Mustang ace was the USAAF’s George Preddy, whose final tally stood at 26.333, 23 scored with the P-51, when he was shot down and killed by friendly fire on Christmas Day 1944 during the Battle of the Bulge.

In China and the Pacific Theater

In 1943, P-51B joined the American Volunteer Group. In early 1945, P-51C, D and K variants also joined the Chinese Nationalist Air Force. These Mustangs were provided to the 3rd, 4th and 5th Fighter Groups and used to attack Japanese targets in occupied areas of China. The P-51 became the most capable fighter in China while the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force used the Ki-84 Hayate against it.

The P-51 was a relative latecomer to the Pacific Theater. This was due largely to the need for the aircraft in Europe, although the P-38s Twin-engine design was considered a safety advantage for long over-water flights. The first P-51s were deployed in the Far East later in 1944, operating in close-support and escort missions, as well as tactical photo reconnaissance. As the war in Europe wound down, the P-51 became more common: eventually, with the capture of Iwo Jima, it was able to be used as a bomber escort during B-29 missions against the Japanese homeland.

The P-51 was often mistaken for the Japanese Ki-61 Hien in both China and Pacific because of its similar appearance.

Expert Opinions

Chief Naval Test Pilot and C.O. Captured Enemy Aircraft Flight Capt. Eric Brown, CBE, DSC, AFC, RN, tested the Mustang at RAE Farnborough in March 1944, and noted, "The Mustang was a good fighter and the best escort due to its incredible range, make no mistake about it. It was also the best American dogfighter. But the laminar flow wing fitted to the Mustang could be a little tricky. It could not by no means out-turn a Spitfire. No way. It had a good rate-of-roll, better than the Spitfire, so I would say the plusses to the Spitfire and the Mustang just about equate. If I were in a dogfight, I’d prefer to be flying the Spitfire. The problem was I wouldn’t like to be in a dogfight near Berlin, because I could never get home to Britain in a Spitfire!"

Luftwaffe Experten were confident that they could outmaneuver the P-51 in a dogfight. Kurt Bühligen, the third-highest scoring German fighter pilot of the Second World War on the Western Front, with 112 victories, later recalled that "We would out-turn the P-51 and the other American fighters, with the (Bf) ’109’ or the (Fw) ’190’. Their turn rate was about the same. The P-51 was faster than us but our munitions and cannon were better."

Post-World War II

In the aftermath of World War II, the USAAF consolidated much of its wartime combat force and selected the P-51 as a "standard" piston-engine fighter, while other types, such as the P-38 and P-47, were withdrawn or given substantially reduced roles. As the more advanced (P-80 and P-84) jet fighters were introduced, the P-51 was also relegated to secondary duties.

In 1947, the newly-formed USAF Strategic Air Command employed Mustangs alongside F-6 Mustangs and F-82 Twin Mustangs, due to their range capabilities. In 1948, the designation P-51 (P for pursuit) was changed to F-51 (F for fighter), and the existing F designator for photographic reconnaissance aircraft was dropped because of a new designation scheme throughout the USAF. Aircraft still in service in the USAF or Air National Guard (ANG) when the system was changed included: F-51B, F-51D, F-51K, RF-51D (formerly F-6D), RF-51K (formerly F-6K), and TRF-51D (two-seat trainer conversions of F-6D’s). They remained in service from 1946 through 1951. By 1950, although Mustangs continued in service with the USAF after the war, the majority of the USAF’s Mustangs had become surplus to requirements and placed in storage, while some were transferred to the Air Force Reserve (AFRES) and the Air National Guard (ANG).

From the start of the Korean War, the Mustang once again proved useful. A substantial number of stored or in service F-51Ds were shipped, via aircraft carriers, to the combat zone and were used by the USAF, and the Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF). The F-51 was used for ground attack, fitted with rockets and bombs, and photo-reconnaissance, rather than being as interceptors or "pure" fighters. After the first North Korean invasion, USAF units were forced to fly from bases in Japan, and the F-51Ds, with their long range and endurance, could attack targets in Korea that short-ranged F-80 jets could not. Because of the vulnerable liquid cooling system, however, the F-51s sustained heavy losses to ground fire. Because of its lighter structure, and a shortage of spare parts, the newer, faster F-51H was not used in Korea.

Mustangs continued flying with USAF and ROKAF fighter-bomber units on close support and interdiction missions in Korea until 1953, when they were largely replaced as fighter-bombers by USAF F-84s, and by United States Navy (USN) Grumman F9F Panthers. Other air forces and units using the Mustang included the Royal Australian Air Force’s (RAAF)’s 77 Squadron, which flew Australian-built Mustangs as part of British Commonwealth Forces Korea. The Mustangs were replaced by Gloster Meteor F.8s in 1951. The South African Air Force’s (SAAF)’s 2 Squadron used U.S. built Mustangs as part of the U.S. 18th Fighter Bomber Wing, and had suffered heavy losses by 1953, after which 2 Squadron converted to the F-86 Sabre.

F-51s flew in the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard throughout the 1950’s. The last American USAF Mustang was F-51D-30-NA (AF 44-74936), which was finally withdrawn from service with the West Virginia Air National Guard in late 1956 and retired to what was then called the Air Force Central Museum, although it was briefly reactivated to fly at the 50th anniversary of the Air Force Aerial Firepower Demonstration at the Air Proving

North American P-51D Mustang/RAF Mustang IV Specifications and Performance Data

Type

Wings

Fuselage

Tail Unit

Landing Gear

Power Plant

Accommodation

Armament

Dimensions

Weights

Performance (Packard V-1650-7 engine)

References