| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

1903 Wright “Flyer”

Single-engine twin-screw single-place pioneer biplane

Archive Photos

1903 Wright “Flyer”, c.1985 on display at the National Air &Space Museum, Washington, DC (photo copyright © 1985 by John Shupek)

1903 Wright “Flyer”, c.2003 on display at the EAA AirVenture Museum, Oshkosh, Wisconsin (9/12/2003 photo copyright © 2003 by Skytamer Images by John Shupek)

1903 Wright “Flyer”, c.2003 on display at the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan (9/24/2003 photo copyright © 2003 by Skytamer Images by John Shupek)

1903 Wright “Flyer” (replica), c.2003 on display at the Kalamazoo Aviation Heritage Museum, Portage, Michigan (9/29/2003 photo copyright © 2003 by Skytamer Images by John Shupek)

1903 Wright “Flyer”, c.2003 on display at the National Air &Space Museum, Washington, DC (2/20/2004 photo by Jim Hough)

1903 Wright Flyer

The Wright Flyer, often retrospectively referred to as “Flyer I” and occasionally “Kitty Hawk”, was the first powered aircraft designed and built by the Wright brothers. It was the first successful powered, piloted, controlled heavier-than-air aircraft.

Design and Construction

The Flyer was based on the Wrights' experience testing gliders at Kitty Hawk between 1900 and 1902. Their last glider, the 1902 Glider, led directly to the design of the Flyer.

The Wrights built the aircraft in 1903 using 'giant spruce' wood as their construction material. Since they could find no suitable automobile engine for the task, they commissioned their employee Charlie Taylor to build a new design from scratch. A sprocket chain drive, borrowing from bicycle technology, powered the twin propellers, which were also made by hand.

The Flyer was a canard biplane configuration. The pilot flew lying on his stomach on the lower wing with his head toward the front of the craft. He steered by moving a cradle attached to his hips. The cradle pulled wires which warped the wings and turned the rudder simultaneously. The Flyer's "runway" was a track of 2 × 4s stood on their narrow end, which the brothers nicknamed the "Junction Railroad."

Flight Tests at Kitty Hawk

Upon returning to Kitty Hawk in 1903, the Wrights completed assembly of the “Flyer” while practicing on the 1902 Glider from the previous season. On December 14, 1903, they felt ready for their first attempt at powered flight. They tossed a coin to decide who would get the first chance at piloting, and Wilbur won the toss. However, he pulled up too sharply, stalled, and brought the “Flyer” Back down with minor damage.

1903 Wright “Flyer”

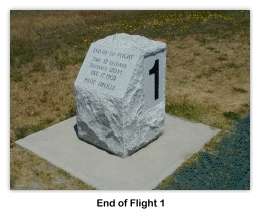

The repairs for the abortive first flight took three days, so that the “Flyer” was ready again on December 17. Since Wilbur had already had the first chance, Orville took his turn at the controls. His first flight lasted 12 seconds for a total distance of 120 feet (36.5 meters).

| 17 December 1903 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Flight No.1 | 120 ft. | 12 seconds | Orville Wright |

| Flight No.2 | 175 ft. | 12 seconds | Wilbur Wright |

| Flight No.3 | 200 ft. | 15 seconds | Orville Wright |

| Flight No.4 | 852 ft. | 59 seconds | Wilbur Wright |

Taking turns, the Wrights made four brief, low-altitude flights on that day. The flight paths that day were all essentially straight; turns were not attempted. Every flight of the aircraft on December 14 and 17 ... under very difficult conditions on the 17th ... ended in a bumpy and unintended "landing". The last, by Wilbur, after a flight of 59 seconds that covered 852 feet (260 meters), broke the front elevator supports, which the Wrights hoped to repair for a possible four-mile flight to Kitty Hawk village. Soon after, a heavy gust picked up the Flyer and tumbled it end over end, damaging it beyond any hope of quick repair.

In 1904, the Wrights continued refining their designs and piloting techniques in order to obtain fully controlled flight. Major progress toward this goal was achieved in 1904 and even more decisively with the modifications during the 1905 program, which resulted in a 39-minute, 24 mile nonstop circling flight by Wilbur on October 5. While the 1903 Flyer was clearly a historically important test vehicle, its near-mythical status in American imagination has obscured its place as part of a continuing development program that eventually led to the Wrights' mastery of controlled flight in 1905.

The Influence of the “Flyer”

The Flyer series of aircraft were the first to achieve controlled heavier-than-air flight, but some of the mechanical techniques used to accomplish this were not influential for the development of aviation as a whole, although the intellectual achievements were. The Flyer design depended on wing-warping and a forward horizontal stabilizer, features which would not scale and produced a hard-to-control aircraft. However, the Wrights' pioneering use of "roll control" by twisting the wings to change wingtip angle in relation to the airstream led directly to the more practical use of ailerons by their imitators, such as Curtiss and Farman. The Wrights' original concept of simultaneous coordinated roll and yaw control, rear rudder deflection, which they discovered in 1902, perfected in 1903-1905, and patented in 1906, represents the solution to controlled flight and is used today on virtually every fixed-wing aircraft. Other features that made the Flyer a success were highly efficient wings and propellers, which resulted from the Wrights' exacting wind tunnel tests and made the most of the marginal power delivered by their early "homebuilt" engines; slow flying speeds (and hence survivable accidents); and an incremental test/development approach. The future of aircraft design, however, lay with rigid wings, ailerons and rear control surfaces.

After a single statement to the press in January 1904 and a failed public demonstration in May, the Wright Brothers did not publicize their efforts, and other aviators who were working on the problem of flight, notably Santos Dumont, were thought by the press to have preceded them by many years. Indeed, several short heavier-than-air powered flights had been made by other aviators before 1903, leading to controversy about precedence. The Wrights, however, claimed to be the first of these which was 'properly controlled'.

The issue of control was correctly seen as critical by the Wrights, and they acquired a wide American patent intended to give them ownership of basic aerodynamic control. This was fought in both American and European courts. European designers, however, were little affected by the litigation and continued their own development. The legal fight in the U.S., however, had a crushing effect on the nascent American aircraft industry, and by the time of World War I, the U.S. had no suitable military aircraft and had to purchase French and British models.

The “Flyer” After Kitty Hawk

The Wright Brothers returned home to Dayton for Christmas after the flights of the Flyer. While they had abandoned their other gliders, they realized the historical significance of the Flyer. They crated it and shipped it Back to Dayton, where it stayed in storage for 9 years. It was inundated in the Great Dayton Flood in March 1913.

In 1910 the Wrights first made attempts to exhibit the Flyer in the Smithsonian Institution but talks fell through with the ensuing lawsuits against Glenn Curtiss and the Flyer may have been needed as repeated evidence in court cases. In 1916, Orville brought the Flyer out of storage and prepared it for display at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Wilbur had died in 1912.) He replaced parts of the covering, the props, and the engine's crankcase, crankshaft, and flywheel. The crankcase, crankshaft and flywheel had been sent to the Aero Club of America for an exhibit in 1906 and were never returned to the Wrights.

Debate with the Smithsonian

The Smithsonian Institution refused to give credit to the Wright Brothers for the first powered, controlled flight of an aircraft. Instead, they honored the former Smithsonian Secretary Samuel Pierpont Langley, whose 1903 tests of his own Aerodrome on the Potomac were not successful. In 1914, Glenn Curtiss flew a heavily modified Aerodrome from Keuka Lake, N.Y., providing the Smithsonian a basis for its claim that the aircraft was the first powered, heavier than air flying machine "capable" of manned flight. Due to the legal patent battles then taking place, recognition of the 'first' aircraft became a political as well as an academic issue.

In 1925, Orville attempted to shame the Smithsonian into recognizing his accomplishment by threatening to send the “Flyer” to the Science Museum in London. The threat did not have its intended effect, and the “Flyer” went on display in the London museum in 1928. During the Second World War, it was moved to an underground vault 100 miles from London where EnglanD’s other treasures were kept safe from the conflict.

In 1942 the Smithsonian Institution published a list of the Curtiss modifications to the Aerodrome and a retraction of its long-held claims for the craft. The next year, Orville agreed to return the “Flyer” to the United States. The “Flyer” stayed at the Science Museum until a replica could be built, based on the original. This change of heart by the Smithsonian is also mired in controversy - the “Flyer” was sold to the Smithsonian under several contractual conditions, one of which reads:

"Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities administered for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright Aeroplane of 1903, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight."

Some aviation buffs, particularly those who promote the accomplishments of pioneer aviator Gustave Whitehead, have commented that this agreement renders the Smithsonian unable to make properly unbiased academic decisions concerning any prior claims of 'first flight'.

The “Flyer” was put on display in the Arts and Industries Building of the Smithsonian on December 17, 1948, 45 years after the aircraft's only flights. Orville did not live to see this, as he died in January of that year. In 1976, it was moved to the Milestones of Flight Gallery of the new National Air and Space Museum. It resided in an exhibit of "The Wright Brothers and the Invention of the Aerial Age," where it stayed until October, 2006.

1985 Restoration

In 1981, discussion began on the need to restore the Flyer from the aging it sustained during years on display. During the ceremonies celebrating the 78th anniversary of the first flights, Mrs. Harold S. Miller, one of the Wright brothers' nieces, presented the Museum with the original covering of one wing of the “Flyer”, which she had received in her inheritance. She expressed her wish to see the aircraft restored.

The fabric covering on the aircraft at the time, which came from the 1927 restoration, was discolored and marked with water spots. Metal fasteners holding the wing uprights together had begun to corrode, marking the nearby fabric. Work began in 1985. The restoration was supervised by Senior Curator Robert Mikesh and assisted by Wright Brothers expert Tom Crouch. Museum director Walter J. Boyne decided to perform the restoration in full view of the public. The wooden framework was cleaned, and corrosion on metal parts removed. The covering was the only part of the aircraft replaced. The new covering was more accurate to the original than that of the 1927 restoration. To preserve the original paint on the engine, the restorers coated it in inert wax before putting on a new coat of paint. The effects of the 1985 restoration were supposed to last 75 years before another restoration would be required.

Flyer Reproductions

A number of individuals and groups have attempted to build reproductions of the Wright Flyer for demonstration or scientific purposes. In 1978, 23-year-old Ken Kellett built a replica Flyer in Colorado and flew it at Kitty Hawk on the 75th and 80th anniversaries of the first flight there. Construction took a year and cost $3,000.

As the 100th anniversary on December 17, 2003 approached, the U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission along with other organizations opened bids for companies to recreate the original flight. The Wright Experience, led by Ken Hyde, won the bid and painstakingly recreated replicas of the original Flyer plus many of the prototype gliders and kites as well as several subsequent Wright aircraft. The completed “Flyer” replica was brought to Kitty Hawk and pilot Kevin Kochersberger attempted to recreate the original flight at 10:35 AM December 17, 2003 from Kill Devil Hill. Although the aircraft had previously made several successful test flights, sour weather, rain, and weak winds prevented a successful flight on the actual anniversary date.

Numerous non-flying replicas are on display around the United States and across the world, making this perhaps the most replicated single aircraft in history.

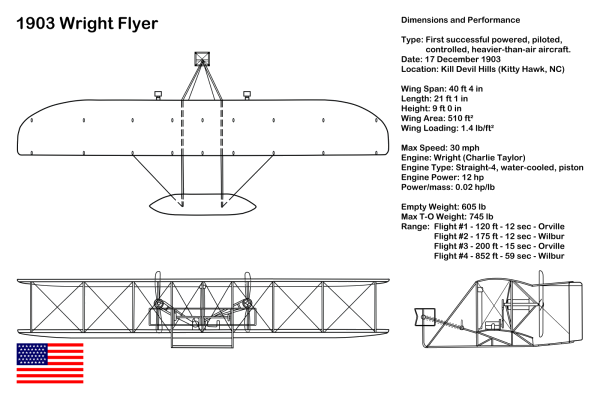

Specifications (Wright Flyer)

| 1903 Wright Flyer | |

|---|---|

| Country of Origin: | United States of America |

| Type: | First successful powered, piloted, controlled heavier-than-air aircraft |

| Manufacturer: | Orville & Wilbur Wright, Dayton, Ohio |

| Accommodation: | One |

| First Flight: | 17 December 1903 |

| Powerplants | |

| No. Engines: | One |

| Engine Manufacturer: | Wright (Charlie Taylor) |

| Engine Designation: | Straight-4, water-cooled, piston engine |

| Engine Power: | 12 hp (9 kW) |

| Power/mass: | 0.02 hp/lb (30 W/kg) |

| Weights | |

| Empty Weight: | 605 lb (274 kg) |

| 745 lb (338 kg) | |

| Wing loading: | 1.4 lb/ft² (7 kg/m²) |

| Performance | |

| Maximum Speed: | 30 mph (48 km/h) |

| Range: | n/a |

| Service ceiling: | n/a |

| Rate of climb: | n/a |

| Dimensions | |

| Wingspan: | 40 ft 4 in (12.29 m) |

| Height: | 9 ft 0 in (2.74 m) |

| Length: | 21 ft 1 in (6.43 m) |

| Wing Area: | 510 ft² (47 m²) |

References

Copyright © 1998-Present, Skytamer Images, Whittier, California

All rights reserved