| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

1980 “Aces in Action” (ZB9-61)

Nabisco Foods Ltd., United Kingdom

Series Title: “Aces in Action”

British Trade Index No.: ZB9-61

Issued by: Nabisco Foods Ltd.

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Year issued: 1980

Packaged with: Nabisco Shredded Wheat

Type of card: Square airplane 3-view hologram card

Number of Cards: 5

Numbering: 1 to 5 on reverse side

Card Dimensions: 47.8 × 47.8 mm

Checklist: Checklist

Overview

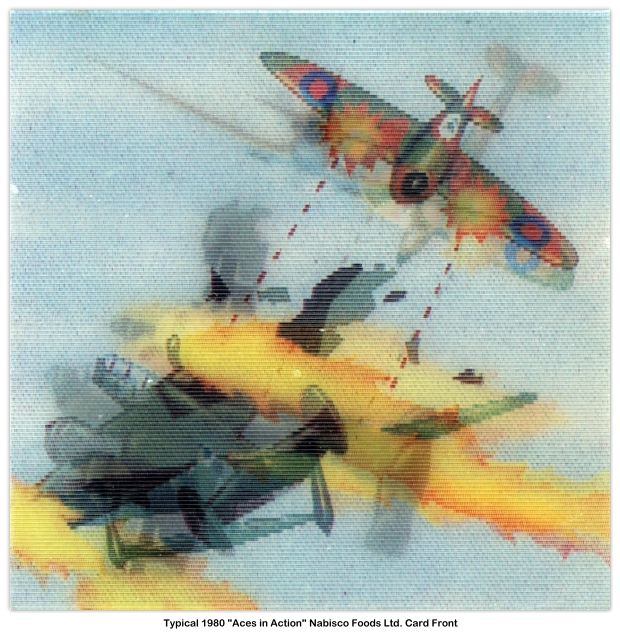

During 1980, Nabisco Foods Ltd., United Kingdom, issued their “Aces in Action” 5-card airplane set. The “Aces in Action” 5-card set was issued to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Battle of Britain. The 5-card set honors the accomplishments of five British pilots that served during the Battle of Britain during August and September of 1940. The cards themselves are square and rather small measuring only 47.8 × 47.8 mm. The fronts of the cards are color holograms depicting the Battle of Britain sorties of five RAF pilots. Each of the holograms contained three separate action images when viewed by changing the viewing angle of the card. The instructions on the back to the cards say “TILT CARD TO AND FRO”, which yields the three different action views. Each of the holograms shows a RAF “Hurricane” or “Spitfire” dispatching Luftwaffe fighters and bombers. The British Trade Index number for the set is ZB9-61.

The backs of the cards are in black and white and start with a RAF roundel in the upper left-hand corner. The set title “Aces in Action” starts off a vertical stack of information that includes: (a) The card number; (b) The card title, which is actually a description of the action taking place on the hologram; (c) A detailed description of the sortie; (d) A a statement of the series length “Collect all five cards in the series”; and (e) a bottom line with viewing instructions “TILT CARD TO AND FRO” and a copyright tag “IPM LONDON”. A sample card is shown below.

The Cereal Box

A very special thanks to Allison Piearce for providing the following 1980 Nabisco Shredded Wheat “Aces in Action” cereal box images.

The 1980 Nabisco Shredded Wheat breakfast cereal box shown above, supplies some interesting clues to why this particular set of airplane cards are so scarce. The cereal box itself appears to have been printed on 4 August 1980. One of the side panels as a mail order offer for two Airfix 1/48 scale model airplanes, the Supermarine “Spitfire Mk.V” and the Messerschmitt 109E. However, this particular offer on the side panel was only valid through 31 December 1980. This would suggest that the “Aces in Action” 3 in 1 “Magic Picture Cards” may have had only a five to six-month production run, or may have been offered during the entire year of 1980 in celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Battle of Britain.

Secondly, another factor that influenced the scarcity of these cards was the individual “Aces in Action” cards contained in the box appear to not have been identified. Therefore, little Winston had only two options to obtain the full set of 5-cards: (a) trade cards with friends, or (b) eat a lot of the Nabisco Shredded Wheat for breakfast. Any clarification on this would certainly be appreciated. The following two narratives from the side panel and the back of the box provide a wonderful insight about the issuance of the “Aces in Action” 5-card set.

Side Panel Narrative

“Battle of Britain Anniversary — In the summer of 1940, the men and machines the Royal Air Force were tested as never before, or since, in the Battle of Britain. To mark the anniversary of that historic battle, Nabisco is proud to pay tribute to the RAF and the courage of its pilots with a unique series of commemorative picture cards.

YOUR MAGIC PICTURE

Each Magic Picture Card contains three scenes. Move the card slowly to and fro to recapture - one at a time - three moments from a real encounter in the skies of Britain in 1940.

COLLECT ALL 5 CARDS IN A SERIES

Relive the excitement of the pilots’ daunting challenge as the battle sequences come to life in your hands. Collect all five picture cards and see how the spirit of the RAF triumphed forty years ago. The same proud tradition lives on in today’s Royal Air Force.”

Box Back Narrative

“The Battle of Britain was probably the most significant conflict in the history of modern warfare for it occurred at a time when Germany seemed invincible in the air and on land. In 1940, they advanced westwards across Europe, undefeated, conquering first Denmark and Norway, then Belgium, Holland and France. The German command thought they could smash Britain who had retreated from Dunkirk in May 1940. History and the RAF were to prove otherwise.

All the single-engine “Spitfires” and “Hurricanes” which the RAF could muster were outnumbered over 3 to 1 by German aircraft when the Battle began on 10th July 1940. The most critical phase of the Battle began on 13th August - code named “Eagle Day” by the Germans. Then the Luftwaffe mounted the start of their all-out attack on the south coast of England, but Britain’s defenses proved impenetrable. On the 15th September alone the RAF destroyed 60 enemy planes, and by the end of October 1940, the German offensive was called off in defeat.

The price of victory was high. Many lives were lost and 915 British planes destroyed. But the Germans were wiped from the skies of Britain losing a total of 1,733 aircraft. Some of the planes which fought in that famous Battle are pictured below.”

The back of the cereal box shows the following two RAF and two Luftwaffe aircraft in action: (1) Supermarine “Spitfire Mk.I.A” (RN-D), (2) Hawker “Hurricane Mk.I” (LE-D), (3) Dornier Do.17Z-2 (A+EZ), and (4) a Messerschmitt Me.109E (<+-) going down in flames.

Image-Guide [1]

The following images shown the fronts and backs of the 1980 “Aces in Action” 5-card set issued by Nabisco Foods Limited, United Kingdom. If the images appear to be a little fuzzy, it’s because they are hologram images which are themselves multi-dimensional. Our scanner can only look at one of the three images. All of the card images have been computer enhanced for presentation purposes. We have also included the original 600-dpi scans of the fronts and backs of each of the five cards. Behind each thumbnail image is a 600-dpi computer enhanced image which you may access.

| 1980 “Aces in Action”

Nabisco Foods Ltd, UK Original 600-dpi Scans | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1b | 2 | 2b | 3 | 3b | 4 | 4b | 5 | 5b | Cereal Box Front | Cereal Box Back |

Checklist

| 1980 “Aces in Action”

Nabisco Foods Ltd, UK Checklist | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sqn. Lr. “Sailor” Malan leading No. 74 (Spitfire) Squadron attacks a Dornier Do.17 — 13th of August 1940. | |

| 2 | Flt. Lt. Nicholson in a Hurricane of No. 249 Squadron destroys an Me.110 — 16th August 1940. | |

| 3 | Flt. Lt. McArthur No. 609 (Spitfire) Squadron, engages the infamous ‘Stukas’ (JU.87s) — 8th August 1940. | |

| 4 | Sqn. Lr. Gleave, No. 253 (Hurricane) Squadron intercepts Luftwaffe Me.109s — 30th August 1940. | |

| 5 | Sgt. “Ginger ” Lacy, No. 501 (Hurricane) Squadron, destroys a Heinkel He.111 — 13th September 1940. | |

“The Aces”

Adolph Gysbert (Sailor) Malan[4] DSO & Bar, DFC & Bar, RNR, better known as “Sailor Malan”, was a South African World War II fighter pilot and flying ace in the Royal Air Force who led No. 74 Squadron RAF during the Battle of Britain. He finished his fighter career in 1941 with 27 destroyed, 7 shared destroyed and 2 unconfirmed, 3 probables and 16 damaged. At the time he was the RAF’s leading ace, and one of the highest scoring pilots to have served wholly with Fighter Command during World War II.

Royal Air Force: In 1935 the RAF started the rapid expansion of its pilot corps, for which Malan volunteered. He learned to fly in the Tiger Moth at an elementary flying school near Bristol, flying for the first time on 6 January 1936. Commissioned an acting pilot officer on 2 March, he completed training by the end of the year, and was sent to join 74 Squadron on 20 December 1936. He was confirmed as a pilot officer on 6 January 1937, and was appointed to acting flight commander of ‘A’ Flight, flying Spitfires, in August. He was promoted to acting flying officer on 20 May 1938 and promoted to substantive flying officer on 6 July. He received another promotion to acting flight lieutenant on 2 March 1939, six months before the outbreak of war.

Second World War - Battle of Barking Creek: No. 74 Squadron saw its first action only 15 hours after war was declared, sent to intercept a bomber raid that turned out to be returning RAF planes. On 6 September 1939, “A” Flight was scrambled to intercept a suspected enemy radar track and ran into the Hurricanes of No. 56 Squadron RAF. Believing 56 to be the enemy, Malan ordered an attack. Paddy Byrne and John Freeborn downed two RAF aircraft, killing one officer, Montague Hulton-Harrop, in this friendly fire incident, which became known as the Battle of Barking Creek. At the subsequent courts-martial, Malan denied responsibility for the attack. He testified for the prosecution against his own pilots stating that Freeborn had been irresponsible, impetuous, and had not taken proper heed of vital communications. This prompted Freeborn’s counsel, Sir Patrick Hastings to call Malan a bare-faced liar. Hastings was assisted in defending the pilots by Roger Bushell, who, like Malan, had been born in South Africa. A London barrister and RAF Auxiliary pilot, Bushell later led the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III. The court ruled the entire incident was an unfortunate error and acquitted both pilots.

Dunkirk: After fierce fighting over Dunkirk during the evacuation of Dunkirk on 28 May 1940, Malan was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross having achieved five “kills”. During this battle he first exhibited his fearless and implacable fighting spirit. In one incident he was able to coolly change the light bulb in his gunsight while in combat and then quickly return to the fray. During the night of 19/20 June Malan flew a night sortie in bright moonlight and shot down two Heinkel He.111 bombers, a then unique feat for which a bar to his DFC was awarded. On 6 July, he was promoted to the substantive rank of flight lieutenant.

Malan and his senior pilots also decided to abandon the “vic” formation used by the RAF, and turned to a looser formation (the “finger-four”) similar to the four aircraft Schwarm the Luftwaffe had developed during the Spanish Civil War. Legend has it that on 28 July he met Werner Môlders in combat, damaging his plane and wounding him, but failing to bring him down. Recent research has suggested however that Môlders was wounded in a fight with No. 41 Squadron RAF.

On 8 August, Malan was given command of 74 Squadron and promoted to acting squadron leader. This was at the height of the Battle of Britain. Three days later, on 11 August, action started at 7 am when 74 was sent to intercept a raid near Dover, but this was followed by another three raids, lasting all day. At the end of the day, 74 had claimed to have shot down 38 aircraft, and was known from then on as “Sailor’s August the Eleventh”. Malan himself simply commented, “thus ended a very successful morning of combat.” He received a bar to his DFC on 13 August.

On the ground, Malan earned a reputation as an inveterate gambler who often owed his subordinates money. Malan was older than most of his charges and although sociable and relaxed off-duty, he spent most of his time with his wife and family living near Biggin Hill. He soon developed a flying routine of leading the first sortie of the day, then handing the squadron to a subordinate while he stayed on the ground to perform the Squadron commander’s administration. Despite frosty relations after the Battle of Barking Creek he would often give command of the squadron to John Freeborn (himself an ace), showing Malan’s ability to keep the personal and professional separate.

Malan commanded 74 Squadron with strict discipline and did not suffer fools gladly, and could be high-handed with sergeant pilots (many non-commissioned pilots were joining the RAF at this time). He could also be reluctant to hand out decorations, and he had a hard-and-fast yardstick via which he would make recommendations for medals: six kills confirmed for a Distinguished Flying Cross, twelve for a bar to the D.F.C.; eighteen for a Distinguished Service Order.

On 24 December, Malan received the Distinguished Service Order, and on 22 July 1941, a bar to the Order. On 10 March 1941 he was appointed as one of the first wing leaders for the offensive operations that spring and summer, leading the Biggin Hill Wing until mid-August, when he was rested from operations. He finished his active fighter career in 1941 with 27 kills destroyed, 7 shared destroyed and 2 unconfirmed, 3 probables and 16 damaged, at the time the RAF’s leading ace, and one of the highest scoring pilots to have served wholly with Fighter Command during World War II. He was transferred to the reserve as a squadron leader on 6 January 1942.

After tours to the USA and the Central Gunnery School, Malan was promoted to temporary wing commander on 1 September 1942 and became station commander at Biggin Hill, receiving a promotion to war substantive wing commander on 1 July 1943. Malan remained keen to fly on operations, often ignoring standing orders for station commanders not to risk getting shot down. In October 1943 he became officer commanding No. 19 Fighter Wing, RAF Second Tactical Air Force, then commander of the No. 145 (Free French) Wing in time for D-day, leading a section of the wing over the beaches during the late afternoon.

Wing Commander Eric James Brindley Nicolson [5], VC, DFC, was a fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. Nicolson was 23 years old and a flight lieutenant in No. 249 Squadron during the Second World War when he was awarded the Victoria Cross. On 16 August 1940 having departed RAF Boscombe Down near Southampton, Nicolson’s Hawker Hurricane was fired on by a Messerschmitt Bf.110, injuring the pilot in one eye and one foot. His engine was also damaged and the petrol tank set alight. As he struggled to leave the blazing machine he saw another Messerschmitt, and managing to get back into the bucket seat, pressed the firing button and continued firing until the enemy plane dived away to destruction. Not until then did he bail out, and he was able to open his parachute in time to land safely in a field. On his descent, he was fired on by members of the Home Guard, who ignored his cry of being a RAF pilot.

James Henry Gordon McArthur[6] DFC, was born in Tynemouth on 12th February 1913. He became a civil pilot in the 1930’s and was awarded Aero Certificate 12614 at Redhill Aero Club on 5th March 1935. At one time he held the London to Baghdad speed record. He took an RAF Short Service Commission in May 1936.

On 18th July he was posted to 9 FTS at Thornaby and was confirmed as a Pilot Officer on 11th October. He then joined the Station Flight at Aldergrove on 14th January 1937 and was promoted to Flying Officer on 11th May. On 1st October 1938 he was posted to the Experimental Section, Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough as a test pilot. McArthur was posted to 238 Squadron at Middle Wallop as a Flight Commander in June 1940, having become a Flight Lieutenant on 11th May, before joining 609 at Middle Wallop as ‘B’ Flight Commander on 1st August 1940 under S/Ldr. Darley.

On 8th August while flying “Spitfire” R6977 he destroyed two Junkers Ju.87 “Stukas” off the Isle of Wight. He destroyed a Messerschmitt Me.110 on the 11th, again in R6977, 15 miles SSE of Swanage. Still in R6977 he claimed a probable Me.110 on the 12th and a Me.109 on the 13th.

On 15th August he destroyed two Me.110’s in R6769. He claimed another Me.110 destroyed on the 25th in X4165 and on 7th September he destroyed a Dornier Do.17. He claimed a further Do.17 destroyed on the 15th in R6979. After this action he suffered an oxygen failure at 25,000 ft. Attacked by Me.109’s he lost consciousness and came to just in time to pull out of a high-speed dive at a low altitude. The damage to his ears was to require future hospital treatment but in the meantime he destroyed a Me.110 on the 25th.

Because of the damage to his ears, McArthur had to hand over command of “B” Flight to F/Lt. J Dundas, after which he was not allowed to fly above 5,000 feet and in consequence was not able to return to operations.

Group Captain Thomas Percy (Tom) Gleave[7] CBE was a British fighter pilot during the Battle of Britain. He was shot down in his “Hurricane” the summer of 1940 and grievously burned. He was one of the first patients treated by Sir Archibald McIndoe at the Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead, and became the first and only Chief Guinea Pig.

In 1930 he was commissioned into the RAF where he excelled; by 1933 he was a member of the RAF aerobatic team. After a period as a flying instructor he joined RAF Bomber Command on 1 January 1939.

At the outbreak of war Gleave requested a return to RAF Fighter Command, which was granted. By June 1940 he was in command of 253 Squadron, flying “Hurricanes”. Command was handed to Squadron Leader H. Starr in August 1940, but Gleave resumed command when Starr was shot down on 31 August. Gleave’s tally by the time he was shot down was five Messerschmitt Bf.109s (in a single day) and one Junkers Ju.88.

Gleave was shot down on his first sortie after restoration of his command, on 31 August 1940, and badly burned. Initially treated at Orpington Hospital, he regained consciousness underneath a bed during an air raid. His wife was called to his bedside and asked the heavily bandaged Gleave “what on earth have you been doing with yourself?” “I had a row with a German” was his characteristically laconic reply, and this became the title of the book he wrote under the pseudonym “RAF Casualty”, published in 1941.

He was transferred to East Grinstead where McIndoe reconstructed his nose. He recovered sufficiently to be returned to non-flying duties and briefly commanded RAF Northolt before taking over RAF Manston, from where he dispatched the six Fairey “Swordfish” of 825 Squadron in their attempt to sink the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen. He was then seconded to the planning group for what became “Operation Overlord” and promoted to Group Captain. He served as Eisenhower’s Head of Air Plans at SHAEF from 1 October 1944 to 15 July 1945 and was then Senior Air Staff Officer, RAF Delegation to France, from 1945 to 1947.

He was finally invalided out of the RAF in 1953, and returned to East Grinstead for further reconstructive surgery. He then joined the Historical Section of the Cabinet Office where he remained for the next thirty years, being elected a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and becoming Air Historian and deputy chairman to the Battle of Britain Fighter Association.

As a prominent member of the Guinea Pig Club, Gleave is discussed in numerous books about McIndoe’s work, including “Faces from the Fire” and “McIndoe’s Army”, and he wrote a monograph I had a Row with a German on his experiences. He was interviewed for the 2002 drama documentary “The Guinea Pig Club” and is discussed in most histories of the Guinea Pigs. He is credited as a technical and tactical advisor for the 1969 film “Battle of Britain”.

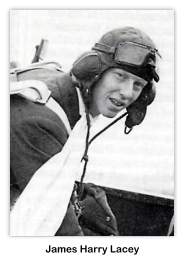

James Harry Lacey[8], DFM & Bar was one of the top scoring Royal Air Force fighter pilots of the Second World War and was the second highest scoring RAF fighter pilot of the Battle of Britain, behind Pilot Officer Eric Lock of No. 41 Squadron RAF. Lacey was credited with 28 enemy aircraft destroyed, five probables and nine damaged.

Lacey joined the RAFVR (Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve) in January 1937 as a trainee pilot at Perth, Scotland. In 1938, he then took an instructor’s course, becoming an instructor at the Yorkshire Flying School, accumulating 1,000 hours of flight time before the war. Called up at the outbreak of war, he joined No. 501 Squadron RAF. On 10 May 1940, the Squadron moved to Bétheniville in France where Lacey experienced his first combat. On the afternoon of 13 May over Sedan, he destroyed a Heinkel He.111 of KG.53 and an escorting Messerschmitt Bf.109 on one sortie, followed by a Messerschmitt Bf.110 later in the afternoon. He claimed two more Heinkel He.111s on 27 May, before the squadron was withdrawn to England on 19 June, having claimed nearly 60 victories. On 9 June, his aircraft was damaged in combat and he crash landed and almost drowned in a swamp. During his operational duties in France, he was awarded the French Croix de guerre.

Flying throughout the Battle of Britain with No. 501 based at Gravesend or Croydon, Lacey became one of the highest scoring pilots of the battle. His first kill of the battle was on 20 July 1940, when he shot down a Bf.109E of Jagdgeschwader 27. He then claimed a destroyed Junkers Ju.87 and a “probable” Ju.87 on 12 August along with a damaged Bf.110 and damaged Do.17 on 15 August, a probable Bf.109 on 16 August. He destroyed a Ju.88, damaged a Dornier Do.17 on 24 August and shot down a Bf.109 of Jagdgeschwader 3 on 29 August. He bailed out unharmed after being hit by return fire from a Heinkel He.111 on 13 August.

On 23 August 1940, Lacey was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal after the destruction of 6 enemy aircraft.

On 30 August 1940, during combat over the Thames Estuary, Lacey shot down a He.111 and damaged a Bf.110 before his “Hurricane” was badly hit from enemy fire. His engine stopped and he decided to glide the stricken aircraft back to the airfield at Gravesend instead of bailing out into the Estuary. A highly successful August was completed when he destroyed a Bf.109 on 31 August. On 2 September 1940, Lacey shot down two Bf.109s and damaged a Do.17. He then shot down another two Bf.109s on 5 September. During a heavy raid on 13 September, he engaged a formation of Kampfgeschwader 55 He.111s over London where he shot down one of the bombers that had just bombed Buckingham Palace. He then bailed out of his aircraft, sustaining slight injuries, as he could not find his airfield in the worsening visibility.

Returning to the action shortly thereafter, he shot down a He.111, three Bf.109s and damaged another on 15 September 1940, one of the heaviest days of fighting during the whole battle, which later became known as “Battle of Britain Day”. During the battle he attacked a formation of 12 Bf.109s, shooting down two before the other had noticed before escaping into cloud. Two days later on 17 September, he was shot down over Ashford, Kent during a dogfight with Bf.109s and bailed out without injury. On 27 September, he destroyed a Bf.109 and damaged a Junkers Ju.88 on 30 September. During October he claimed a probable Bf.109 on 7 October, shot down a Bf.109 on 12 October, another on 26 October and on 30 October, he destroyed a Bf.109 before damaging another. During the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain, Lacey had been shot down or forced to land due to combat no less than nine times. On 26 November 1940, with 23 claims (18 made during the Battle of Britain) Lacey received a Bar to his Distinguished Flying Medal for his continued outstanding courage and bravery during the Battle of Britain. The citation in the London Gazette read: “740042 Sergeant James Harry Lacey, D.F.M., Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, No. 501 Squadron. Sergeant Lacey has shown consistent efficiency and great courage. He has led his section on many occasions and his splendid qualities as a fighter pilot have enabled him to destroy at least 19 enemy aircraft.”

Lacey’s final award for outstanding service during 1940 was a Mention in Despatches announced on 1 January 1941. Lacey was commissioned a pilot officer (on probation) on 25 January 1941 (seniority from 15 January) and promoted to acting flight lieutenant in June. On 10 July 1941, as ‘A’ flight commander, he shot down a Bf.109 and damaged another a few days later on 14 July. On 17 July, he claimed a Heinkel He.59 seaplane shot down and on 24 July, two Bf.109s (by causing them to collide). He was posted away from combat operations during August 1941, serving as a flight instructor with No. 57 Operational Training Unit. He was promoted to War Substantive Flying Officer on 22 September.

During March 1942, Lacey joined No. 602 Squadron, based at Kenley flying the “Spitfire Mk.V” and by 24 March had claimed a Focke-Wulf Fw.190 as damaged. He damaged another Fw.190 on 25 April 1942 before a posting to No. 81 Group as a tactics officer. Promoted to War Substantive Flight Lieutenant on 27 August, in November he was posted as Chief Instructor at the No. 1 Special Attack Instructors School, Milfield.

In March 1943, Lacey was posted to No. 20 Squadron, Kaylan in India before joining 1572 Gunnery Flight in July of the same year to convert from “Blenheims” to “Hurricanes” and then to Republic P-47 “Thunderbolts”. He stayed in India, being posted to command No. 155 Squadron flying the “Spitfire Mk.VIII” in November 1944 and then as commanding officer of No. 17 Squadron later that month. While based in India, Lacey claimed his last aircraft on 19 February 1945, shooting down a Japanese Army Air Force Nakajima Ki.43 “Oscar” with only nine 20 mm cannon rounds.

Lacey was one of the few RAF pilots on operational duties on both the opening and closing day of the war. His final tally was 28 confirmed, four probable and nine damaged.

References